Rules of the game. A. Dolzhansky - A Short Course in Harmony Examples of Chord Sequences

CONTENTFrom the author 3

Lesson 1. Introduction. Voice Conduct in Major

Lesson 2. Voicing in major (continued)

Lesson 3. Voicing in major (end)

Lesson 4. Voicing in a minor key

Lesson 5. Theoretical foundations of harmony (theory of harmonic functions)

Lesson 6. Composing problems in a major key. General principles,

Lesson 7. Composing problems in a major key (continued)

Lesson 8. Composing problems in a major key (second continuation)

Lesson 9. Composing problems in a major key (end)

Lesson 10. Basic minor chords,

Lesson 11. Natural minor chords

Lesson 12. Composing problems in harmonic major

Lesson 13. Modulation theory

Lesson 14. Perfect diatonic modulation of the 1st degree of kinship from major

Lesson 15. Perfect diatonic modulation of the 1st degree of kinship from minor

Lesson 16. Perfect diatonic modulation of the 2nd degree of kinship from major

Lesson 17. Perfect diatonic modulation of the second degree from minor

Lesson 18. Perfect diatonic modulation of the third degree of kinship from major and minor

Lesson 19. Imaginary enharmonic modulation

Lesson 20. Diminished seventh chords in major

Lesson 21. Diminished seventh chords in minor

Lesson 22. Perfect enharmonic modulation (II and III degrees of affinity) through a dominant seventh chord

Lesson 23. Perfect melodic-chromatic modulation (of all degrees of kinship) from major and minor

Lesson 24. Perfect diatonic or enharmonic modulation via diminished seventh chord

Lesson 25. Deviations of the first degree of kinship in major

Lesson 26. Deviations of the first degree of kinship in minor

Lesson 27. Repeated deviations of the first degree of kinship in major and minor

Lesson 28. Secondary dominants in major

Lesson 29. Secondary dominants in minor

Lesson 30. Tonal plans

Addition

Application. Accordica

Methodological notes

In memory of Azary Ivanovich Ivanov

FROM THE AUTHOR

“A Short Course in Harmony” is intended for persons familiar with elementary music theory and intending to expand their musical theoretical knowledge professionally or amateurly.

The book is based on a pedagogical method first implemented by the author in the first years of the performing departments of the 1st Leningrad Music School named after M. P. Mussorgsky in the second half of the 1930s. This method, besides the author, was repeatedly used in the specified school and in other special educational institutions by a number of teachers (Az. I. Ivanov, A. Ya. Koralsky, A. N. Sokhor, A. A. Kholodilin and others), and also in music lovers' circles.

The book sets out a complete theoretical course of harmony, the completion of which is based on simplified, compared to conventional teaching methods, practical skills.

Thanks to some special presentation techniques, the “Short Course” is designed to be mastered within 30 lessons (weeks), that is, in one academic year.

After completing the “Short Harmony Course,” the student can deepen his knowledge and skills in more detailed special systems. In this case, classes using these systems will be significantly easier and can be dramatically accelerated compared to the usual time frame.

On the other hand (which especially concerns music lovers, but also professional performers), having mastered the “Short Course in Harmony”, the student will be sufficiently prepared to move directly to the analysis of musical works, and in practical terms, to arrangements for various instrumental and vocal compositions.

When studying harmony, music lovers have to take into account not only the different level of abilities and degree of preparation of the student, but also the degree of his interest in the subject,

the scope and depth of knowledge that he wants to acquire. Unlike vocational training, there cannot be standard norms and requirements, since much depends on the will and desires of the student.

In this case, practical skills can be endlessly varied. Nevertheless, experience shows that they can be reduced to certain varieties, and among music lovers interested in harmony, certain categories can be established: from those seeking to learn the content of the course only in general terms, to those wishing to study it in a business-like manner, thoroughly, in order to deepen their understanding music, in a serious sense to continue familiarization with various aspects of musicology. To meet the needs of amateurs of various categories, at the end of the book (see pp. 162 - 163) special ways to facilitate (reduce and simplify) the course are proposed. If the course is completed independently, it is desirable to have periodic supervision from the supervisor.

The book as a whole consists of:

The main course (presented in the form of 30 lessons), Supplement (expanding the main course and designed for students of increased activity),

Appendix (containing the necessary information for those starting to study harmony without sufficient knowledge of elementary music theory).

Methodological notes (addressed to the leader and explaining various ways to use the “Short Course in Harmony”).

The author thanks in advance everyone who will send their feedback on the “Short Course in Harmony” to the address: Leningrad, D-11, Inzhenernaya str., 9. Leningrad branch of the publishing house “Music”. The author will also try to satisfy the needs of those who send him questions that arose in connection with reading the proposed book.

(...)

VI. LAST FIVE LESSONS

After completing the main course (lessons 1 - 30), the last five lessons (31 - 35) should be devoted to summarizing everything learned and preparing for exams, and “rehearsals”.

Consistent with this goal, each homework assignment should correspond substantially to the written examination paper (see p. 158), and each class activity should be conducted in the form of an oral examination (see p. 159).

In the first hour of the lesson, while checking homework, unlike lessons 1 - 30, all students should not write notes, but, having received several theoretical exam questions, prepare answers to them.

In the second hour of the lesson, instead of a regular lecture, the teacher arranges a trial test of exam answers to the questions asked at the beginning of the lesson. At the same time, it is important that students, having recalled and summarized the theoretical part of the course as a whole, become accustomed to the volume and content of the answer to each individual question.

During these repeated classes, one person should be called to the board for an “examination” answer in front of the rest of the students, who at this time turn into an “examination committee.”

If the answer turns out to be incomplete or incorrect, you should invite one of the other students to supplement or correct it.

In this case, it is better that it is not the designated teacher, but the student who wishes to answer.

Here, for the first time during the course of harmony, students answer the course orally in front of their comrades, so the danger of “infecting” each other with errors does not disappear. Therefore, the teacher must, at the end of the answer to each individual exam question, “sum up the debate” and briefly list those points that must necessarily be contained in an oral answer on this question in the exam.

Classroom practice sessions (lessons 31 - 35) do not relieve students of the need to review the course at home to prepare for the exam. For such repetition, it is best to first read the entire “short course of harmony” in a row, and then work through individual questions from the notes, referring to the book as needed.

VII. EXAM

Completion of the course must necessarily end with an exam, regardless of whether the course was studied according to the plan of the educational institution or at the personal request of amateurs.

The exam is needed not only as a test of knowledge, but as a special form of completion of the course. Examination requirements, their elaboration, first of all, represent a complete repetition of the course, that is, a new (final) completion of the course as a whole, a condensed assimilation of it as a system of theoretical principles and practical skills, is of exceptional importance.

Conducting an exam ensures the strength of knowledge, such an understanding of the subject in which any forgotten position can be restored on the basis of the logic of the course, on the basis of its theory.

VIII. A WRITTEN EXAM

The examination must consist of a written paper and an oral response.

In the written exam, the examinee must write three problems:

2 small (8 - 12 bars) single-key problems (one in major, one in minor), applying the given chords and deviations to them, and

1 large (16 - 24 bars) problem, built according to a given tonal plan (see examples 277, and also 303).

In one-tone problems, you should require the use of certain second chords, quarter-sixth chords, altered subdominant chords, any rare chords (for example, natural minor chords or diminished seventh chords), auxiliary dominants.

In a large modulation problem, a mandatory tonal plan must be proposed, indicating in some cases the methods of transition from one tonality to another (enharmonic through a certain chord, chromatic, etc.). (See assignment for lesson 30.)

There should be a total of 12 different tickets in this exam with two theoretical questions (A and B) in each: one from the area of harmony before modulation, the other from modulation theory.

Theoretical questions on the harmony course

A.

1. Harmonic gravitation and fifth circuit (1).

2. Complex cadence circuit, its formation and elements (2)

3. Functions of side triads (4).

4. Functions of seventh chords (5).

5. Chord inversion functions (6).

6. Ways to develop a complex cadence circuit (3).

7. Alteration and altered chords in major (11).

8. Diminished seventh chords in major (9).

9. Functions of harmonic minor chords (7).

10. Functions of natural minor chords (8).

I. Alteration and altered chords in minor (12).

12. Diminished seventh chords in minor (10).

B.

1. Modulation, its elements and classification (1).

2. Modulation of the first degree of kinship from major (12).

3. Modulation of the first degree of kinship from minor (I).

4. Modulation of the second degree of kinship from major (10).

5. Modulation of the second degree of kinship from minor (9).

6. Modulation of the third degree of kinship (3).

7. Enharmonic modulation through dominant seventh chord (2).

8. Modulation via diminished seventh chord (6).

9. Melodic-chromatic modulation (4).

10. Deviations in major (8).

11. Deviations in minor (5).

12. Side dominants (7).

Here the questions are presented in logical order. The number of the ticket on which it is placed is indicated in parentheses after each question. Thus, ticket Ш 1 will contain the following questions:

A. Harmonic gravitation and the fifth circuit. B. Modulation, its elements and classification; in ticket number 4:

A. Functions of seventh chords. B. Melodic-chromatic modulation, etc.

To prepare to answer these questions, you should give as much time as it takes one or two students to answer orally.

In addition, during the oral exam, the student must answer 2-3 pre-prepared technical questions without preparation. For example:

1. What tonalities of I, II, III degree of relationship does such and such tonality have?

2. To what degree of relationship are such and such two tones?

3. Through what diminished seventh chord and what kind of modulation can be accomplished from such and such a key to such and such?

Finally, in the oral examination, the student must demonstrate piano playing skills in harmonic exercises and skills in harmonic analysis.

Requirements for performing harmonic exercises on the piano are not given here, since they largely depend on the student’s progress in playing and should, essentially, be taught in a piano class. Most often, they can be reduced to playing in all keys of various predetermined cadences.

The requirements for harmonic analysis are also not given.1 The existing anthologies of O. L. and S. S. Skrebkov and V. Berkov can be used here. Information on individual issues can be obtained in the book: A. Dolzhansky. "A Brief Musical Dictionary". It is very useful to use pieces for analysis that are not difficult to perform, but meaningful and varied in terms of harmony, for example from Tchaikovsky’s “Children’s Album.”

1 The author is currently working on compiling a textbook on analysis.

X. ABOUT PREPARING A STUDENT TO TAKE A HARMONY COURSE

To take a harmony course, you must have sufficient knowledge of elementary music theory, both theoretically and practically. The student must be able to:

1. Construct any interval (pure, large, small, increased, decreased, as well as some twice increased or twice decreased intervals) from any given sound (using simple and double accidentals).

2. Determine the width and quality of the proposed interval.

3. Construct triads and seventh chords of any structure from any given sound (using also simple and double accidentals).

4. Construct triads and seventh chords of all levels and all types in major (natural and harmonic) and minor (natural, harmonic and melodic), in keys of up to seven key signs.

5. The same - in four-voice addition on two staves.

It is desirable that all of the listed types of tasks be completed by the student no lower than “good” (4.4+).

Since not all pedagogical systems for teaching a course in elementary music theory include the listed teachings, this part of the course in elementary music theory is provided in the appendix to this book (see p. 140, “Accordics”) for study before the main lessons.

If in the course of elementary music theory the chords should be taught at a fairly slow pace, then in the course of harmony it is recommended to devote no more than three lessons to it (from among the reserve ones).

This is explained by the fact that in elementary theory the chords are taken at the end of the school year before the final exam. After finishing it, there is no time left to repeat the course and consolidate it in the students’ memory. On the contrary, long summer holidays usually come, which contribute to the loss of recently acquired skills that have not yet had time to “settle” sufficiently in the student’s mind.

Accordics become aware of harmony at the beginning of the school year. Having mastered it, the student will continue to practice using chords for a long time and not only consolidate, but also develop the acquired skills.

In order to ensure that the speed of completion of this section does not damage the strength of the skills, it is recommended to complete as many exercises as possible for each of the above types of tasks (as indicated in the Supplement), fully using the time allotted for completing homework (2 hours per week). week).

The emphasis should be on building chords (not defining them). Practice shows that four to six hours (that is, time to complete two or three homework) is enough to build several hundred chords and in the future, when taking a harmony course, you will not experience any particular difficulties from insufficient knowledge of chords.

Thus:

a) a small number of types of tasks, b) a large number of identical (same type) exercises, c) a short period of study will certainly ensure the development of practical skills in the field of chords, necessary for starting harmony classes.

It goes without saying that, depending on the state of knowledge of the students, such preliminary repetition of chords is possible not in three, but in two lessons or even in one lesson.

If the student has completed chords in full before starting harmony lessons, then special repeated lessons are not required and the study of harmony should begin right from the first lesson.

XI. INDIVIDUALIZATION OF CLASSES

The individual inclinations and capabilities of a student often do not appear immediately, but gradually, starting, of course, with completing tasks for independently composing problems.

At the beginning, the student cannot tear himself away from the tables for lessons 7 - 12, but at some point, the “suddenly” understanding (namely not knowledge, but understanding) of these tables frees him from using them, and he begins to compose problems on his own, relying on on the logic of theory, and not on recipes. At this moment, he develops his own taste: a predilection for certain chordal means or harmonic turns, an independent, and not imitative selection of them. Sometimes the student invents his own means.

The task of pedagogical tact is to support and direct these creative quests. Advice in this regard goes beyond the scope of the Short Course.

If in order to complete the main course one must adhere to the main text of 30 lessons, then if one deviates from it, the teacher must determine a plan for such deviation in each individual case.

XII. EXTENDED AND SHORTENED COURSE COMPLETION

Expansion of the course is possible only on an individual basis with students capable enough for this, and most importantly, sufficiently purposeful.

In this case, you should first of all rely on the Addendum, using its individual paragraphs by no means in the same sequence as they are. presented, and in the order, quantity, volume as it will be found appropriate.

In addition, for students who firmly intend to study harmony after this course in an in-depth plan, it is useful as early as possible, in addition to (and even instead of) the writing of chords that the author adheres to, to use the arrangement of two voices on each line (soprano-f-alto on the top, tenor -? bass on the bottom) with stems in different directions.

Experience has also shown that capable and enthusiastic students master the course at a faster pace, which is possible, however, not in a regular group setting, but with a limited number of students or with individual lessons. In this case, some lessons are easily learned two in one lesson. For example, 3 and 4, 5 and 6, 13 and 14, 16 and 17, 20 and 21, 25 and 26, 28 and 29. With maximum use of this opportunity, the entire course can be learned not in 30, but in approximately 20 lessons. This is especially applicable to students who already have some kind of humanitarian profession or who have a penchant for composing music.1

In all cases, extended (as well as accelerated) courses should be undertaken carefully and gradually and only with students truly suited for the purpose. Otherwise, such an attempt will not only not take place on its own, but will also spoil the usual assimilation of the course.

1 In 1962, doctor K.F. Tovstoles completed the entire course in 20 lessons. His exam task is given on page 126.

Facilitation of the course is achieved by reducing its volume.

The following main cases are possible here.

1. Going through some sections only in theoretical terms without performing practical tasks in these sections. This includes lessons 16 - 19, 22 - 24, that is, sections concerning modulations of distant degrees of kinship and complex (non-diatonic) modes.

It is possible to go through these sections (all or some of them) only theoretically, so that in homework at this time composing problems in the same key and composing modulations of the first degree of kinship would continue until lesson 25.

2. A more simplified method of completing the course is to completely abandon written work, limiting it to reading theoretical provisions and analyzing the given samples. This path is appropriate for students of a certain mindset, whose theoretical inclinations allow them, without practical skills, to apply an understanding of harmonic logic directly to analysis, bypassing the stage of assimilating it through written work.

3. Finally, all sorts of “intermediate” techniques for shortening individual of the lessons listed above are acceptable.

In this case, the teacher must rework the corresponding tasks given at the end of the shortened lessons.

At the same time, it must be remembered that mastering the course will not be complete, will not allow you to move on to the study of the next musical theoretical subject, and therefore is acceptable only for amateurs.

XIV. PERFORMANCE OF TASKS IN THE CLASSROOM

It is highly desirable that all (or the most important) harmonic examples written on the blackboard during the lecture be performed not only on the piano, but also on instruments, with a drawn-out sound, and best of all, by a choir of students. In order not to waste extra time on the formation of such ensembles, you should form a string or wind quartet (for example, of three clarinets and a bassoon) in the very first lesson (before solving the first digitalization), as well as (necessarily) four choir parts from the students of the group - best three batches of female and one batch of male votes.

In the future, a choir organized in this way should always be ready to sing new material written by the leader on the blackboard (including the best, most successful work completed by students on homework).

To save time, it is useful to write harmonic samples illustrating lecture material not on the board, but on pre-prepared posters.

Choral singing of harmonic patterns is the most important technique for teaching harmony.

Dmitry Nizyaev

The classical course of harmony is based on a strictly four-voice texture, and this has a deep justification. The fact is that all music as a whole - texture, form, laws of melody construction, and all conceivable means of emotional coloring - comes from the laws of human speech, its intonations. Everything in music comes from the human voice. And human voices are divided - almost arbitrarily - into four registers in height. These are soprano, alto (or "mezzo" in vocal terminology), tenor and bass. All the countless varieties of human timbres are just special cases of these four groups. Simply, there are male and female timbres, and there are high and low ones among both - these are the four groups. And, strange as it may seem, four voices - different voices - is exactly the optimal number necessary to voice all the consonances existing in harmony. Coincidence? God knows... One way or another, let's take it for granted: Four voices are the basis.

Any texture, no matter how complex and cumbersome you create it, will essentially be four voices; all other voices will inevitably duplicate the roles of the main four. Interesting note: the timbres of instruments fit perfectly into the four-voice scheme.

So, rule one: we will do everything in four voices.

Secondly, since we do not pursue arrangement goals, but only study the interaction of consonances (just as mathematics does not mean physical apples or boxes by numbers, but operates with numbers in general), then we do not need any tools. Or rather, anyone capable of producing four notes at once will do, the default being a piano. In addition, for the sake of the purity and transparency of our thinking, we will write examples and exercises in the so-called “harmonic” texture, that is, vertical “pillars”, chords. Well, perhaps occasionally it will be possible to give a more texturally developed example to show that the law being studied is valid in such conditions. Rule three: exercises or illustrations on harmony are written on a piano (i.e. double) staff, and the voices are distributed equally among the lines: on the top - soprano and alto, on the bottom - tenor and bass. The spelling of stems in these conditions differs from the traditional one: regardless of the position of the note head, the stem is always directed upward for the soprano and tenor, and always downward for the rest. So that the voices in your eyes are not confused. Fourth: if we need to name a polyphonic consonance with words, the notes are listed from bottom to top, indicating the sign (even if it is in the key), okay? Fifthly - this is VERY important - never replace, say, C-sharp with D-flat in harmony, even though it is the same key. Firstly, these notes still have different meanings (they belong to different keys, have different gravity, etc.), and secondly, despite the generally accepted opinion, they actually even have different pitches! If we start talking about tempered and natural tuning (I don’t know yet whether this will happen), then you will see that C-sharp and D-flat are completely different notes, there is nothing in common. So let’s agree for now: such a substitution of one sign for another can only happen “for a reason,” and not at will. This is called “enharmonism” - we will have such a topic in the future. Well, let's begin by praying...

All the patterns studied by harmony are absolutely repeated in any key; they simply do not depend on the name of the tonic. Therefore, in order to express one or another consideration that is suitable for any key, we cannot use the names of notes. For convenience, the scale of any key is provided with numbers that replace the names of the notes, and these conventional numbers are called steps. That is, the very first, main sound of the scale - it doesn’t matter what note it is, and what mode it is - becomes the first step, then the count goes up to the seventh step (in C major, for example, it’s “B”), after which it follows first again. We will depict the numbers of steps in Roman numerals "I - VII". And if we discover that, for example, between D and F (II and IV degrees of C major) there is an interval of a minor third, then you can rest assured that the same interval will be between the II and IV degrees of any major, no matter what impossible signs there are nor were they at the key. Convenient, isn't it?

SODINARY

We already know that a triad is a combination of three notes arranged in thirds. To make you feel at ease among triads, I advise you to practice constructing triads from arbitrary notes both up and down. Moreover, it would be good to be able to do this simply instantly, combining three methods: pressing them on the keys (even imaginary ones), singing them in order to memorize their colors, and singing them silently, in the imagination. This is how an “inner ear” is cultivated, which will help you have sounding music right in your head, continue working right on the street, and in addition will give you the opportunity, rarely available to anyone, to “lead”, “sing”, and track several melodic lines in your mind simultaneously (after all, with your voice -You won't cover more than one melody at a time!).

You have already been told that there are four types of triads: major, minor, augmented and diminished. But these are just words, names. But are these words associated in your mind with coloring? What emotions does the word “reduced” evoke in you?

“F” is quite firmly on its feet, but is not averse to going to “E”. Because “F” is the prima, the main sound of the chord, and if it is resolved into “E”, it will become just the third of a new chord - and it’s more pleasant for anyone to be the first guy in the village than the small fry in the city! “La” is an unstable and indecisive sound, although it smiles. Judge for yourself: “la” is not the leader here either, and after permission, he will have nothing better to do than to be the furthest from the tonic. However, “A” is still a major, major third, and therefore radiates optimism. "Before" is a completely different matter. She is above everyone else, she is on the right path, she will become a queen (that is, tonic) and at the same time she will not have to lift a finger. “Do” will remain in its place, and honor and respect will come to it on its own. Here is the event “fa-la-do... mi-sol-do”, containing many emotions and adventures at once.

You can guess that in a different key, when the F major triad is on a different level, each of its notes will have completely different colors and emotions, and will gravitate differently. Let's draw this conclusion - learning how this or that chord is built is still not enough! The most interesting thing with this chord will happen only in the key.

And from the point of view of harmony, any triad should be called not major or minor - this is not the main thing now - but a triad of one or another level, or one or another functional group. Moreover, it can be built not only by thirds, don’t you agree?

Let's summarize: in both modes the triads of the main degrees (I, IV, V) coincide with the main mode. The mediant and submediant (III, VI) have the opposite mode.

The triads of the introductory steps (these are II and VII, adjacent to the tonic) just need to be remembered; they do not fit into the symmetrical scheme. So that you don’t have to return to the question of where and what triads are located in the key, practice:

1. Find the tonic of a triad (for example, the triad “B-flat - D - F, major: in what keys can it occur; what is the tonic if this triad is the VI degree? Or the III? Or the IV?).

2. Construct triads of any degrees in any key. For a while! Tips: For now, construct triads in the classical form, as you learned in music theory lessons. Don’t invent any appeals just yet. For now, the task is to find out what notes a chord consists of, but the location of the notes, even in what octave, is not important yet. Secondly, try not to get too used to C major, try to work in any key. It depends on your flexibility and independence from the number of key signs whether you will be able to apply at least something in life. No information should be stored in your head in the form of note names. Otherwise, knowing that “do-e-sol” is a major triad, you do not recognize the same triad in the notes “a-flat - do - e-flat”, understand? Be more versatile! In the next lesson, when you are already clicking these steps and triads like nuts, we will learn how to connect them with each other and try to color some melody with them.

A musical composition consists of several components - rhythm, melody, harmony.

Moreover, if rhythm and melody are like a single whole, then harmony is what decorates any piece of music, what makes up the accompaniment that you dream of playing on the piano or guitar.

Musical harmony is a set of chords, without which not a single song or piece will be complete, full-sounding.

A play or song without harmony is like an uncolored picture in books for children - it is drawn, but there is no color, no tints, no brightness. That is why violinists, cellists, domrists, and balalaika players play accompanied by an accompanist - unlike these instruments, you can play a chord on the piano. Well, or play domra or flute in an ensemble or orchestra, where chords are created due to the number of instruments.

In music schools, colleges and conservatories there is a special discipline - harmony, where students study all the chords existing in music theory, learn to apply them in practice and even solve harmony problems.

I will not delve into the jungle of theory, but will tell you about the most popular chords used in modern compositions. Often they are the same. There is a certain block of chords that wander from one song to another. Accordingly, a lot of musical works can be performed on one such block.

To begin with, we determine the tonic (the main note in a musical composition) and remember, along with the tonic, the subdominant and dominant. We take a scale step and build a triad from it (one note at a time). Very often they are enough to play a simple piece. But not always. So, in addition to the triads of the main steps, the triads of the 3rd, 2nd and 6th steps are used. Less often – 7th. Let me explain with an example in the key of C major.

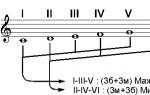

Examples of chord progressions

I put the chords in descending order of their popularity:

C major

- C major, F major, G major (these are the main triads of the mode);

- Li minor (this is nothing more than a triad of the 6th degree);

- E major, less often - E minor (triads of the 3rd degree);

- D minor (2nd degree);

- si – diminished triad of the 7th degree.

And this is another option for using the 6th degree triad in musical compositions:

But the fact is that these musical harmonies are characteristic only if the note DO is taken as the tonic. If suddenly the key of C major is inconvenient for you, or the piece sounds, say, in D major, we simply shift the entire block and get the following chords.

D major

- D major, G major, A major (1st, 4th, 5th steps - main triads)

- B minor (6th degree triad)

- F# major (3rd degree triad)

- E minor (2nd degree)

- to # reduced 7th stage.

For your convenience, I will show a block in a minor key, slightly different degrees are popular there and it can no longer be said that the chords of the 3rd and 2nd degrees are rarely used. Not that rare.

La Minor

A standard set of chords in A minor looks like this

Well, in addition to the standard ones - 1, 4 and 5 steps - the base of any key, the following harmonies are used:

- A minor, D minor, E major (main);

- E seventh chord (related to E major, often used)

- F major (6th degree triad);

- C major (3rd degree triad);

- G major (2nd degree triad);

- A major or A seventh chord (the major of the same name is often used as a kind of transitional chord).

How to find tonic

A question that torments many. And how to determine the tonic, that is, the main tonality from which you need to start when searching for chords. Let me explain - you need to sing or play a melody. The note it ends on is the tonic. And we determine the mode (major or minor) only by ear. But it must be said that in music it often happens that a song begins in one key and ends in another, and it can be extremely difficult to decide on the tonic.

Only hearing, musical intuition and knowledge of theory will help here. Often the completion of a poetic text coincides with the completion of a musical text. Tonic is always something stable, affirming, unshakable. Once the tonic has been determined, it is already possible to select musical harmonies based on the given formulas.

Well, the last thing I would like to say. The flight of creative inspiration of a composer can be unpredictable - seemingly completely unpredictable chords sound harmonious and beautiful. This is already aerobatics. If only the main steps of a scale are used in a musical composition, then this is called a “simple accompaniment.” It is really simple - even a beginner can pick them up with basic knowledge. But more complex musical harmonies are closer to professionalism. That’s why it’s called “picking” chords for a song. So, to summarize:

- We determine the tonic, and for this we play or hum a melody and look for the main note.

- We build triads from all degrees of the scale and try to remember them

- We play chords in the blocks indicated above - that is, standard chords

- We sing (or play) a melody and “pick” a chord by ear so that they create a harmonious and beautiful sound. We start from the main steps; if they are not suitable, we “feel” other triads.

- We rehearse the song and enjoy our own performance.

As a tip, it’s convenient to select musical harmonies along with the sound of the original on a music center, computer or tape recorder. Listen to it several times, and then take a fragment, say 1 verse, and pause it, play it on the piano. Go for it. Selecting musical harmonies is a matter of practice.

Playing guitar. Music theory and harmony - Part 1 (Notes on the guitar neck) May 13th, 2014

Good afternoon, fellow musicians and all those who want to get into playing the guitar.

Having learned to play popular songs with chords and learned simple chord forms, the question often arises: what next?

There is a desire to play a solo part on a sequence of chords or find out why the A6/9 chord is needed.

But many questions arise:

- what notes to play;

- why some notes sound accompanied by accompaniment, while others hurt the ear;

- why in C major they always play D minor and in very rare F sharp minor;

- what is the difference between the C major and C minor scales and in what compositions should they be played;

- what chords to play blues and jazz, hard rock or heavy metal;

and many other hows, whys and whys.

And if you want to play in a group, then at rehearsals you can often hear:

"We play this song in G major, sequence I-VI-IV-V (first, sixth, fourth and fifth)"

Which chords from the sequence are major and which are minor and what are the chords here?? but no one said anything about it “in the yard”)))

Therefore, a modern musician simply needs to know and understand music theory and musical harmony, regardless of the genre that you already play or want to study.

Many guitarists are intimidated by the prospect of learning to read music. And probably many have musician friends who studied at a music school, but did not finish their studies precisely because of difficulties with musical notation. You can often hear from them that notes are boring and difficult. At the same time, examples are set of musicians who do not know sheet music, but nevertheless became stars and play the guitar excellently. And this is partly true. But not many take into account the fact that these people have absolute pitch and have undeniable musical talent.

Many famous musicians did not study at conservatories and music colleges. However, they all put a lot of effort into learning on their own. Self-education is sometimes no less effective than at school, but this requires great desire and self-discipline.

Many self-taught guitarists do not know sheet music and easily play by ear. Such training is achieved through books, various manuals and tutorials, video lessons, as well as through communication with other experienced guitarists and musicians in general. By selecting music by ear, you can gradually develop your skills to a high level.

At the same time, knowledge of notes will be a very useful skill, which will give much more freedom of creative action. For example, world-famous guitarist Steve Vai spends a lot of time flying, and while on a plane he wrote a lot of excellent music. Because to create he only needs inspiration and a notebook.

You need to start learning to play the guitar by studying the notes on the guitar fretboard. This is the basis - like the alphabet in a language.

You cannot read a word without knowing the letters it consists of.

It’s the same in music - knowing the notes, you can build a scale. Chords can be constructed from scales. By taking a sequence of chords, you can play or select any composition.

By using different modes, you can “color” the composition with the appropriate mood, from deep sadness to bright and joyful colors.

Adviсe

1. Your guitar must be tuned!!! no matter what kind of guitar you have, Custom Shop or standard instrument. I recommend contacting a good guitar maker. He will rebuild the "meznura" of the guitar - this is extremely necessary so that the notes sound correctly, regardless of what fret they are played on. Also, during the learning process, the brain will remember the correct intervals, and on an untuned and untuned guitar, a “porridge” will form in the head. Adjust the height of the strings above the fingerboard - you should feel comfortable holding them and this should not distract you from playing. If you plan to use a tremolo, then after using it the guitar must remain in tune, in other words, after raising or lowering the strings, they must return to their original tuning.

2. Tune your guitar using a tuner. Now you can buy it in any design - be it a pedal or a clip on the neck of a guitar. You can buy a tuner with a built-in metronome, which will come in handy for independent practice.

Theory

Notes in music are designated by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet - namely:

A(la) B(si) C(before) D(re) E(mi) F(F) G(salt).

In Russian musical literature, the note B is often designated as N, and B-flat lowered by half a tone IN. To avoid confusion, we will use the international system of notation.

We begin studying notes on the fretboard in standard tuning by studying notes on open strings:

1st string - note E(mi)

2nd string - note B(si)

3rd string - note G(salt)

4th string - note D(re)

5th string - note A(la)

6th string - note E(mi)

It should be noted that the note E(E) on the 6th string is two octaves lower than the same note on the 1st string.

Exercise (horizontal movement along one string)

Consistently play notes on the 1st string E(E) starting from the open string up the fingerboard:

then down the fretboard in reverse order.

Please note that the note E(E) on an open string is different from the note E(E) on the 12th fret one octave. For convenience, there are two dots on the guitar neck at the 12th fret.

move on to the 2nd string IN(si):

We also play sequentially, first up, then down the fingerboard.

3rd string G(salt)

4th string D(re)

5th string A(la)

on the 6th string E(E) we play notes on the same frets as on the 1st string

Now you can combine the notes from all six strings into one diagram and expand it across the entire surface of the fretboard:

At the initial stage of learning, it is always convenient to have such a diagram on hand in printed or electronic form as a cheat sheet.

We study on our own

So we studied the location of the main notes on the guitar fretboard without accidentals.

Please note that the distance between adjacent notes is 2 frets or one tone, with the exception of pairs of notes E (mi) F (fa) And B (si) C (do)- the distance between them is one fret or half a tone.

The question arises - which note(s) is on the second fret between notes WITH(C) 1st fret and D(d) 3rd fret on 2nd string?

You probably heard something from school music lessons about the signs “sharp” and “flat” and that within one scale there are 7 notes and 12 sounds.

Sign #

(sharp) - raises the note by half a step

Sign b(flat) - lowers the note by a semitone

In our case, on the second fret of the 2nd string the note will correspond WITH#(C sharp) or Db(D-flat), depending on the chosen key and musical mode. For example, in the G major scale the note will appear F#(F-sharp), and in the F-minor scale - notes Ab(A-flat) Bb(B-flat) Db(D-flat) and Eb(E-flat).

Thus, we can fill in the missing frets with notes that are raised or lowered by half a tone, respectively.

In the next part, we will arrange the studied notes into the C major scale and study its location on the guitar neck in various positions.

to be continued...

What's Inside the Book:

Practice

Here are just some of the skills you will gain:

Understanding different styles of harmony: blues, jazz, rock, pop

Ability to create chord progressions: tonal and modal

Knowledge of the laws of interaction of chords with each other in various systems

Practical skills in constructing any fingerings and chord forms

Universal chord substitution techniques

Understanding the role of the guitar in different styles

Development of chord playing technique

Understand deviations and modulations

Learn to build quarter chords

Learn what three sounds are and how to use them in practice

See methods for working on guitar texture

- ——Introduction.

- ——Alphanumeric notation and Roman numeral system.

- ——Recommendations for mastering harmony

- ——Triad chords and fingerings

- ——Inversions of triads and fingerings

- ——Voicing and its role in guitar practice

- —— Fundamentals of a functional system

- —— All chords of the scale and their functions

- ——Functional logic minor

- ——Harmonization of scales

- —— Cadances and their varieties

- —— Three types of harmonic motion

- ——Principles of substitutions

- —— Melody harmonization

- —— Free harmonization

- ——Harmonic improvisation

- —— Texture and harmony

- —— Form and harmony

- ——Harmonic sequences

- ——Seventh chords and their classes

- ——Fundamentals of polytonal harmony

- ——Chord alterations

- ——Elements of melody in harmony

- —— Deviations and modulations in guitar harmony

- —— Modal harmony

- —— Features of modern harmony

- —— Triads and synonyms

- —— Quarter chords

- ——Styles at a Glance

- --Conclusion

Bonuses

- Reader of chord progressions (book)

- 17 mind maps on harmony

- Video course Harmony 100: Alphanumeric notation of chords

- Video course: Modulations and deflections

The book “Practical Harmony for the Guitarist” should undoubtedly be a mandatory element in your training, if only for the reason that it will save you a huge amount of time, effort, nerves and money. You don't need to study hundreds of textbooks! I have already done this work for you and collected the entire concentrate of practical information on harmony for the guitarist.

If you want to truly master the guitar, then without knowledge of harmony and the ability to apply it in practice, you are unlikely to achieve your goals.

No textbook will teach you without your efforts, but this book has everything you need for musical growth. All you need to do is read and practice.

Learning harmony for guitarists has never been easier!