Russian field marshals. Generalissimos and Field Marshals of Russia. Into a new era

Brought up in battles

in the midst of stormy weather

The epigraph to this book, containing the biographies of all Russian field marshals without exception, was given by a line from a well-known poem by A.S. Pushkin "Memoirs in Tsarskoye Selo": "You are immortal forever, O giants of Russia, // You were brought up in battles in the midst of abusive bad weather!" And although the poet addressed the generals-companions of Catherine II, his pathos, according to the author, is appropriate in relation to, if not all, then very many bearers of the highest military rank of the Russian Empire.

“In their gigantic millennial work, the builders of Russia relied on three great foundations - the spiritual power of the Orthodox Church, the creative genius of the Russian People and the valor of the Russian Army.”

The truth, cast by the military historian of the Russian abroad, Anton Antonovich Kersnovsky, into an enviably chased formula, is impossible not to accept! And if you remember that it was expressed just a few years before Hitler's attack on the Soviet Union, on the eve of one of the most severe clashes of two civilizations in the history of our people - Slavic-Orthodox and Teutonic-Western European, then you involuntarily think about the indisputable symbolism of what was accomplished by the patriotic historian . He, over ideologies and political regimes, passed on to his compatriots in the USSR from long-gone generations of warriors for the Russian Land, like a relay race, ideas about the eternal foundations and sources of strength of our Motherland.

The presence of the army and armed forces in their ranks is more than natural. The need to repel the aggression of numerous neighbors who wanted to profit from the countless wealth of the country, the interest in expanding borders, the protection of geopolitical interests in various regions of the world forced Russia to constantly keep gunpowder dry. In the 304 years of the Romanov dynasty alone, the country experienced about 30 major wars, including with Turkey - 11, France - 5, Sweden - 5, as well as Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, Prussia (Germany), Iran, Poland, Japan and others countries.

S. Gerasimov. Kutuzov on the Borodino field.

In battle and battle, the soldier wins, but it is known that the mass of even excellently trained fighters is worth little if it does not have a worthy commander. Russia, having shown the world an amazing type of ordinary soldier, whose fighting and moral qualities have become a legend, has also given birth to many first-class military leaders. The battles fought by Alexander Menshikov and Pyotr Lassi, Pyotr Saltykov and Pyotr Rumyantsev, Alexander Suvorov and Mikhail Kutuzov, Ivan Paskevich and Iosif Gurko entered the annals of military art, they were studied and are being studied in military academies all over the world.

Before the formation of a regular army by Peter I in the Moscow kingdom, to designate the post of commander in chief, there officially existed the position of a yard governor, to whom all the troops were entrusted. He excelled over the chief governor of the Big Regiment, that is, the army. In the Petrine era, these archaic titles were replaced by European ranks: the first - Generalissimo, the second - Field Marshal General. The names of both ranks are derived from the Latin "generalis", i.e. "general". The generalship in all European (and later not only) armies meant the highest degree of military ranks, because its owner was entrusted with the command of all branches of the military.

About the Generalissimo in the Military Regulations of Peter I of 1716 it was said as follows: “This rank is only due to the crowned heads and the great possessing princes, and especially to the one whose army is. In his non-existence, this command surrenders over the entire army to his field marshal general. Only three people were awarded this rank in the Russian imperial army: His Serene Highness Prince A.D. Menshikov in 1727, Prince Anton-Ulrich of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (father of the young Emperor Ivan Antonovich) in 1740 and Prince A.V. Suvorov in 1799

The Generalissimo was outside the system of officer ranks. Therefore, the highest military rank was actually Field Marshal General. According to Peter's "Table of Ranks", he corresponded to the civil rank of chancellor and belonged to the 1st class. In the Military Regulations of Peter I, it was legally enshrined as follows: “Field Marshal General or Anshef is the commander of the chief general in the army. Everyone should respect his order and command, because the whole army and the real intention from his sovereign were handed over to him.

"Military Encyclopedia" I.D. Sytina explains the origin of the term "field marshal" in this way: it is based on the combination of the German words "feld" (field) with "march" (horse) and "schalk" (servant). The term "marshal" gradually migrated to France. At first, that was the name of ordinary grooms. But since they were inseparable from their masters during numerous campaigns and hunts, their social position increased dramatically over time. Under Charlemagne (VIII century), marshals, or marshals, were already called persons in command of the convoy. Gradually, they took more and more power into their hands. In the XII century. marshals are the closest assistants to the commanders-in-chief, in the 14th century they were troop inspectors and senior military judges, and in the first third of the 17th century. - top commanders In the 16th century, first in Prussia, and then in other states, the rank of field marshal (field marshal general) appears.

The military charter of Peter I also provided for the Deputy Field Marshal - Field Marshal Lieutenant General (there were only two of them in the Russian army, these are Baron G.-B. Ogilvy and G. Goltz invited from abroad by Peter I). Under the successors of the first Russian emperor, this rank completely lost its significance and was abolished.

From the moment of introduction in the Russian army in 1699, the rank of field marshal general and until 1917 was awarded to 63 people:

in the reign of Peter I:

Count F.A. GOLOVIN (1700)

duke K.-E. CROA de CROI (1700)

Count B.P. SHEREMETEV (1701)

His Serene Highness Prince A.D. MENSHIKOV (1709)

Prince A.I. REPNIN (1724)

during the reign of Catherine I:

Prince M.M. GOLITSYN (1725)

Count J.-K. SAPEGA (1726)

Count Ya.V. BRUCE (1726)

during the reign of Peter II:

Prince V.V. DOLGORUKY (1728)

prince I.Yu. TRUBETSKOY (1728)

in the reign of Anna Ioannovna:

Count B.-H. MINICH (1732)

Count P.P. LASSIE (1736)

in the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna:

Prince L.-I.-V. HESSEN-HOMBURG (1742)

S.F. APRAKSIN (1756)

Count A.B. BUTURLIN (1756)

Count A.G. RAZUMOVSKY (1756)

prince N.Yu. TRUBETSKOY (1756)

Count P.S. SALTYKOV (1759)

in the reign of Peter III:

Count A.I. SHUVALOV (1761)

Count P.I. SHUVALOV (1761)

duke K.-L. HOLSTEIN-BECK (1761)

Prince P.-A.-F. HOLSTEIN-BECK (1762)

Prince G.-L. SCHLEZWIG-HOLSTINSKY (1762)

during the reign of Catherine II:

Count A.P. BESTUZHEV-RYUMIN (1762)

Count K.G. RAZUMOVSKY (1764)

Prince A.M. GOLITSYN (1769)

Count P.A. RUMYANTSEV-ZADUNAYSKY (1770)

Count Z.G. CHERNYSHEV (1773)

Landgrave Ludwig IX of Hesse-Darmstadt (1774)

His Serene Highness Prince G.A. POTEMKIN-TAVRICHESKY (1784)

Prince of Italy, Count A.V. SUVOROV-RYMNIKSKY (1794)

during the reign of Paul I:

His Serene Highness Prince N.I. SALTYKOV (1796)

Prince N.V. REPNIN (1796)

Count I.G. CHERNYSHEV (1796)

Count I.P. SALTYKOV (1796)

Count M.F. KAMENSKY (1797)

Count V.P. MUSIN-PUSHKIN (1797)

schedule. ELMPT (1797)

Duke W.-F. de BROGLY (1797)

during the reign of Alexander I:

Count I.V. GUDOVICH (1807)

Prince A.A. PROZOROVSKY (1807)

His Serene Highness Prince M.I. GOLENISHCHEV-KUTUZOV-SMOLENSKY (1812)

Prince M.B. BARCLY de TOLLY (1814)

duke A.-K.-U. WELLINGTON (1818)

during the reign of Nicholas I:

His Serene Highness Prince P.Kh. WITGENSTEIN (1826)

Prince F.V. AUSTEN-SACKEN (1826)

Count I.I. DIBICH-ZABALKANSKY (1829)

Most Serene Prince of Warsaw,

Count I.F. PASKEVICH-ERIVANSKY (1829)

Archduke Johann of Austria (1837)

His Serene Highness Prince P.M. VOLKONSKY (1843)

Count R.-J. von RADETSKY (1849)

during the reign of Alexander II:

His Serene Highness Prince M.S. VORONTSOV (1856)

Prince A.I. BARYATINSKY (1859)

Count F.F. BERG (1865)

Archduke ALBRECHT-Friedrich-Rudolf of Austria (1872)

Crown Prince of Prussia FRIEDRICH WILHELM (1872)

Count H.-K.-B. von MOLTKE the Elder (1871)

Grand Duke MIKHAIL NIKOLAEVICH (1878)

Grand Duke NIKOLAI NIKOLAEVICH the Elder (1878)

during the reign of Nicholas II:

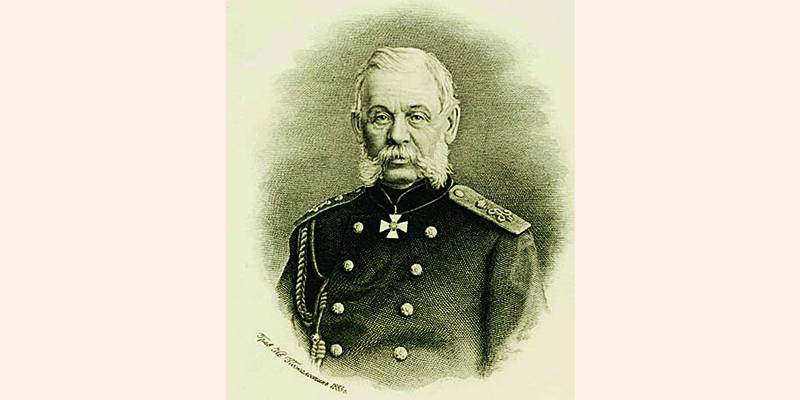

I.V. GURKO (1894)

Count D.A. MILUTIN (1898)

King of Montenegro NICHOLAS I NEGOS (1910)

King of Romania KAROL I (1912)

The young years of Boris Petrovich as a representative of the noble nobility were no different from their peers: at the age of 13 he was granted a room steward, accompanied Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich on trips to monasteries and villages near Moscow, stood at the throne at solemn receptions. The position of stolnik ensured proximity to the throne and opened up wide prospects for promotion in ranks and positions. In 1679, military service began for Sheremetev. He was appointed comrade voivode in the Big Regiment, and two years later - voivode of one of the categories. In 1682, with the accession to the throne of tsars Ivan and Peter Alekseevich, Sheremetev was granted a boyar status.In 1686, the embassy of the Commonwealth arrived in Moscow to conclude a peace treaty. The four members of the Russian embassy included the boyar Sheremetev. Under the terms of the agreement, Kyiv, Smolensk, Left-bank Ukraine, Zaporozhye and Seversk land with Chernigov and Starodub were finally assigned to Russia. The treaty also served as the basis for the Russian-Polish alliance in the Great Northern War. As a reward for the successful conclusion of "Eternal Peace", Boris Petrovich was granted a silver bowl, a satin caftan and 4,000 rubles. In the summer of the same year, Sheremetev went with the Russian embassy to Poland to ratify the treaty, and then to Vienna to conclude a military alliance against the Turks. However, the Austrian emperor Leopold I decided not to burden himself with allied obligations, the negotiations did not lead to the desired results.

After returning, Boris Petrovich is appointed governor in Belgorod. In 1688, he took part in the Crimean campaign of Prince V.V. Golitsyn. However, the first combat experience of the future field marshal was unsuccessful. In the battles in the Black and Green valleys, the detachment under his command was crushed by the Tatars.

In the struggle for power between Peter and Sofia, Sheremetev took the side of Peter, but for many years he was not called to the court, remaining the Belgorod governor. In the first Azov campaign in 1695, he participated in a theater of operations remote from Azov, commanding troops that were supposed to divert Turkey's attention from the main direction of the offensive of Russian troops. Peter I instructed Sheremetev to form an army of 120,000, which was supposed to go to the lower reaches of the Dnieper and tie down the actions of the Crimean Tatars. In the first year of the war, after a long siege, four fortified Turkish cities surrendered to Sheremetev (including Kizy-Kermen on the Dnieper). However, he did not reach the Crimea and returned with troops to Ukraine, although almost the entire Tatar army at that time was near Azov. With the end of the Azov campaigns in 1696, Sheremetev returned to Belgorod.

In 1697, the Great Embassy headed by Peter I went to Europe. Sheremetev was also part of the embassy. From the king, he received messages to Emperor Leopold I, Pope Innocent XII, Doge of Venice and Grand Master of the Order of Malta. The purpose of the visits was to conclude an anti-Turkish alliance, but it was not successful. At the same time, Boris Petrovich was given high honors. So, the master of the order laid the Maltese commander's cross on him, thereby accepting him as a knight. In the history of Russia, this was the first time that a Russian was awarded a foreign order.

By the end of the XVII century. Sweden has become very powerful. The Western powers, rightly fearing her aggressive aspirations, were willing to conclude an alliance against her. In addition to Russia, the anti-Swedish alliance included Denmark and Saxony. Such a balance of power meant a sharp turn in Russia's foreign policy - instead of a struggle for access to the Black Sea, there was a struggle for the Baltic coast and for the return of lands torn off by Sweden at the beginning of the 17th century. In the summer of 1699, the Northern Union was concluded in Moscow.

Ingria (the coast of the Gulf of Finland) was to become the main theater of operations. The primary task was to capture the fortress of Narva (Old Russian Rugodev) and the entire course of the Narova River. Boris Petrovich is entrusted with the formation of regiments of the noble militia. In September 1700, with a 6,000-strong detachment of noble cavalry, Sheremetev reached Wesenberg, but, without engaging in battle, retreated to the main Russian forces near Narva. The Swedish king Charles XII with 30,000 troops approached the fortress in November. November 19, the Swedes launched an offensive. Their attack was unexpected for the Russians. At the very beginning of the battle, foreigners who were in the Russian service went over to the side of the enemy. Only the Semyonovsky and Preobrazhensky regiments held out stubbornly for several hours. Sheremetev's cavalry was crushed by the Swedes. In the battle near Narva, the Russian army lost up to 6 thousand people and 145 guns. The losses of the Swedes amounted to 2 thousand people.

After this battle, Charles XII directed all his efforts against Saxony, considering it his main enemy (Denmark was withdrawn from the war as early as the beginning of 1700). The corps of General V.A. was left in the Baltic states. Schlippenbach, who was entrusted with the defense of the border regions, as well as the capture of Gdov, Pechory, and in the future - Pskov and Novgorod. The Swedish king had a low opinion of the combat effectiveness of the Russian regiments and did not consider it necessary to keep a large number of troops against them.

In June 1701, Boris Petrovich was appointed commander-in-chief of the Russian troops in the Baltic. The king ordered him, without getting involved in major battles, to send cavalry detachments to the areas occupied by the enemy in order to destroy the food and fodder of the Swedes, to accustom the troops to fight with a trained enemy. In November 1701, a campaign was announced in Livonia. And already in December, the troops under the command of Sheremetev won the first victory over the Swedes at Erestfer. 10,000 cavalry and 8,000 infantry with 16 guns acted against the 7,000-strong Schlippenbach detachment. Initially, the battle was not entirely successful for the Russians, since only dragoons participated in it. Finding themselves without the support of infantry and artillery, which did not arrive in time for the battlefield, the dragoon regiments were scattered by enemy grapeshot. However, the approaching infantry and artillery dramatically changed the course of the battle. After a 5-hour battle, the Swedes began to flee. In the hands of the Russians were 150 prisoners, 16 guns, as well as food and fodder. Assessing the significance of this victory, the tsar wrote: "We have reached the point that we can defeat the Swedes; while two against one fought, but soon we will begin to defeat them in equal numbers."

For this victory, Sheremetev is awarded the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called with a gold chain and diamonds and is promoted to the rank of Field Marshal. In June 1702, he already defeated the main forces of Schlippenbach at Hummelshof. As in the case of Erestfer, the Swedish cavalry, unable to withstand the pressure, took to flight, upsetting the ranks of their own infantry, dooming them to destruction. The success of the field marshal is again noted by Peter: "We are very grateful for your labors." In the same year, the fortresses of Marienburg and Noteburg (ancient Russian Oreshek) were taken, and the following year, Nienschanz, Yamburg, and others. Livonia and Ingria were completely in the hands of the Russians. In Estonia, Wesenberg was taken by storm, and then (in 1704) Dorpat. The tsar deservedly recognized Boris Petrovich as the first winner of the Swedes.

In the summer of 1705, an uprising broke out in southern Russia, in Astrakhan, led by archers, who were sent there for the most part after the streltsy riots in Moscow and other cities. Sheremetev is sent to suppress the uprising. In March 1706, his troops approached the city. After the bombing of Astrakhan, the archers surrendered. "For which your work," the king wrote, "the Lord God will pay you, and we will not leave." Sheremetev was the first in Russia to be granted the title of count, he received 2400 households and 7 thousand rubles.

At the end of 1706, Boris Petrovich again took command of the troops operating against the Swedes. The tactics of the Russians, who were expecting a Swedish invasion, boiled down to the following: without accepting a general battle, retreat into the depths of Russia, acting on the flanks and behind enemy lines. Charles XII by this time managed to deprive Augustus II of the Polish crown and put it on his protege Stanislav Leshchinsky, and also to force Augustus to break allied relations with Russia. In December 1707 Charles left Saxony. The Russian army of up to 60 thousand people, commanded by the tsar to Sheremetev, retreated to the east.

From the beginning of April 1709, the attention of Charles XII was riveted to Poltava. The capture of this fortress made it possible to stabilize communications with the Crimea and Poland, where there were significant forces of the Swedes. And besides, the road from the south to Moscow would be opened to the king. The tsar ordered Boris Petrovich to move to Poltava to join up with the troops of A.D. Menshikov and thereby deprive the Swedes of the opportunity to break the Russian troops in parts. At the end of May, Sheremetev arrived near Poltava and immediately assumed the duties of commander in chief. But during the battle, he was the commander-in-chief only formally, while the king led all the actions. Driving around the troops before the battle, Peter turned to Sheremetev: "Mr. Field Marshal! I entrust my army to you and I hope that in commanding it you will act according to the instructions given to you ...". Sheremetev did not take an active part in the battle, but the tsar was pleased with the actions of the field marshal: Boris Petrovich was the first in the award list of senior officers.

In July, he was sent by the king to the Baltic at the head of the infantry and a small detachment of cavalry. The immediate task is the capture of Riga, under the walls of which the troops arrived in October. The tsar instructed Sheremetev to capture Riga not by storm, but by siege, believing that victory would be achieved at the cost of minimal losses. But the raging plague epidemic claimed the lives of almost 10 thousand Russian soldiers. Nevertheless, the bombing of the city did not stop. The capitulation of Riga was signed on July 4, 1710.

In December 1710, Turkey declared war on Russia, and Peter ordered the troops stationed in the Baltic to move south. A poorly prepared campaign, lack of food and inconsistency in the actions of the Russian command put the army in a difficult situation. Russian regiments were surrounded in the area of the river. The Prut, which many times outnumbered the Turkish-Tatar troops. However, the Turks did not impose a general battle on the Russians, and on July 12 a peace was signed, according to which Azov returned to Turkey. As a guarantee of the fulfillment of obligations by Russia, Chancellor P.P. was held hostage by the Turks. Shafirov and son B.P. Sheremeteva Mikhail.

Upon returning from the Prut campaign, Boris Petrovich commands troops in Ukraine and Poland. In 1714 the tsar sent Sheremetev to Pomerania. Gradually, the tsar began to lose confidence in the field marshal, suspecting him of sympathy for Tsarevich Alexei. 127 people signed the death sentence for Peter's son. Sheremetev's signature was missing.

In December 1716 he was released from command of the army. The field marshal asked the king to give him a position more suitable for his age. Peter wanted to appoint him governor-general of the lands in Estonia, Livonia and Ingria. But the appointment did not take place: on February 17, 1719, Boris Petrovich died.

200 years ago, the last Field Marshal of the Russian Empire, Dmitry Milyutin, was born - the largest reformer of the Russian army.

Dmitry Alekseevich Milyutin (1816–1912)

It is to him that Russia owes the introduction of universal military service. For its time, it was a real revolution in the principles of manning the army. Before Milyutin, the Russian army was an estate, its basis was recruits - soldiers recruited from the townspeople and peasants by lot. Now everyone was called to it - regardless of origin, nobility and wealth: the defense of the Fatherland became a truly sacred duty for everyone. However, the Field Marshal became famous not only for this ...

COAT OR UNIFORM?

Dmitry Milyutin was born on June 28 (July 10), 1816 in Moscow. On his paternal side, he belonged to the middle-class nobles, whose surname originated from the popular Serbian name Milutin. The father of the future field marshal, Alexei Mikhailovich, inherited the factory and estates, burdened with huge debts, with which he unsuccessfully tried to pay off all his life. Mother, Elizaveta Dmitrievna, nee Kiselyova, came from an old eminent noble family, Dmitry Milyutin's uncle was Infantry General Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselyov, a member of the State Council, Minister of State Property, and later Russian Ambassador to France.

Alexei Mikhailovich Milyutin was interested in the exact sciences, was a member of the Moscow Society of Naturalists at the University, was the author of a number of books and articles, and Elizaveta Dmitrievna knew foreign and Russian literature very well, loved painting and music. Since 1829, Dmitry studied at the Moscow University Noble Boarding School, which was not much inferior to the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, and Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselev paid for his education. The first scientific works of the future reformer of the Russian army belong to this time. He compiled an "Experience in a Literary Dictionary" and synchronic tables on, and at the age of 14-15 he wrote a "Guide to shooting plans using mathematics", which received positive reviews in two reputable magazines.

In 1832, Dmitry Milyutin graduated from the boarding school, having received the right to the tenth grade of the Table of Ranks and a silver medal for academic excellence. Before him stood a landmark question for a young nobleman: tailcoat or uniform, civilian or military path? In 1833, he went to St. Petersburg and, on the advice of his uncle, entered the 1st Guards Artillery Brigade as a non-commissioned officer. He had 50 years of military service ahead of him. Six months later, Milyutin became an ensign, but the daily shagistics under the supervision of the Grand Dukes exhausted and dulled him so much that he even began to think about changing his profession. Fortunately, in 1835 he managed to enter the Imperial Military Academy, which trained officers of the General Staff and teachers for military schools.

At the end of 1836, Dmitry Milyutin was released from the academy with a silver medal (at the final exams he received 552 points out of 560 possible), promoted to lieutenant and appointed to the Guards General Staff. But the guardsman's salary alone was clearly not enough for a decent living in the capital, even if, as Dmitry Alekseevich did, he eschewed the entertainment of the golden officer youth. So I had to constantly earn extra money with translations and articles in various periodicals.

MILITARY ACADEMY PROFESSOR

In 1839, at his request, Milyutin was sent to the Caucasus. Service in the Separate Caucasian Corps at that time was not just a necessary military practice, but also a significant step for a successful career. Milyutin developed a number of operations against the highlanders, he himself participated in the campaign against the village of Akhulgo - the then capital of Shamil. In this expedition, he was wounded, but remained in the ranks.

The following year, Milyutin was appointed to the post of quartermaster of the 3rd Guards Infantry Division, and in 1843 - chief quartermaster of the troops of the Caucasian Line and the Black Sea. In 1845, on the recommendation of Prince Alexander Baryatinsky, who was close to the heir to the throne, he was recalled to the disposal of the Minister of War, and at the same time Milyutin was elected a professor at the Military Academy. In the characterization given to him by Baryatinsky, it was noted that he was diligent, had excellent abilities and intelligence, exemplary morality, and was thrifty in the household.

Milyutin did not give up scientific studies either. In 1847-1848, his two-volume work "First Experiments in Military Statistics" was published, and in 1852-1853, a professionally executed "History of the War between Russia and France in the reign of Emperor Paul I in 1799" in five volumes.

The last work was prepared by two informative articles written by him back in the 1840s: “A.V. Suvorov as a Commander" and "Russian Generals of the 18th Century". "The History of the War between Russia and France", translated into German and French immediately after publication, brought the author the Demidov Prize of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Shortly thereafter, he was elected a corresponding member of the academy.

In 1854, Milyutin, already a major general, became the clerk of the Special Committee on measures to protect the shores of the Baltic Sea, which was formed under the chairmanship of the heir to the throne, Grand Duke Alexander Nikolayevich. So the service brought together the future Tsar-reformer Alexander II and one of his most effective associates in developing reforms ...

MILYUTIN'S NOTE

In December 1855, when the Crimean War was so difficult for Russia, Minister of War Vasily Dolgorukov asked Milyutin to write a note on the state of affairs in the army. He fulfilled the order, especially noting that the number of armed forces of the Russian Empire is large, but the bulk of the troops are untrained recruits and militias, that there are not enough competent officers, which makes new sets meaningless.

Seeing a new recruit. Hood. I.E. Repin. 1879

Milyutin wrote that a further increase in the army was also impossible for economic reasons, since industry was unable to provide it with everything necessary, and import from abroad was difficult due to the boycott announced by European countries to Russia. Obvious were the problems associated with the lack of gunpowder, food, rifles and artillery pieces, not to mention the disastrous state of transport routes. The bitter conclusions of the note largely influenced the decision of the members of the meeting and the youngest Tsar Alexander II to start peace negotiations (the Paris Peace Treaty was signed in March 1856).

In 1856, Milyutin was again sent to the Caucasus, where he took the post of chief of staff of the Separate Caucasian Corps (soon reorganized into the Caucasian Army), but already in 1860 the emperor appointed him a comrade (deputy) minister of war. The new head of the military department, Nikolai Sukhozanet, seeing Milyutin as a real competitor, tried to remove his deputy from significant affairs, and then Dmitry Alekseevich even had thoughts of resigning to engage exclusively in teaching and scientific activities. Everything changed suddenly. Sukhozanet was sent to Poland, and Milyutin was entrusted with the management of the ministry.

Count Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselyov (1788–1872) - infantry general, minister of state property in 1837–1856, uncle D.A. Milyutin

His first steps in his new post were met with universal approval: the number of ministry officials was reduced by a thousand people, and the number of outgoing papers - by 45%.

ON THE WAY TO A NEW ARMY

On January 15, 1862 (less than two months after assuming a high position), Milyutin submitted to Alexander II a most submissive report, which, in fact, was a program of broad transformations in the Russian army. The report contained 10 points: the number of troops, their recruitment, staffing and management, drill, personnel of the troops, the military judicial unit, food supplies, the military medical unit, artillery, and engineering units.

The preparation of a military reform plan required from Milyutin not only an effort (he worked on the report 16 hours a day), but also a fair amount of courage. The minister encroached on the archaic and much compromised in the Crimean War, but still legendary, covered with heroic legends of the estate-patriarchal army, which remembered both the “Ochakov times”, and Borodino and the capitulation of Paris. However, Milyutin decided on this risky step. Or rather, a number of steps, since the large-scale reform of the Russian armed forces under his leadership lasted almost 14 years.

Training of recruits in Nikolaev time. Drawing by A. Vasiliev from the book by N. Schilder "Emperor Nicholas I. His life and reign"

First of all, he proceeded from the principle of the greatest reduction in the size of the army in peacetime, with the possibility of its maximum increase in the event of war. Milyutin was well aware that no one would allow him to immediately change the recruitment system, and therefore proposed to increase the number of annually recruited recruits to 125 thousand, provided that the soldiers were dismissed “on leave” in the seventh or eighth year of service. As a result, over the course of seven years, the size of the army decreased by 450-500 thousand people, but on the other hand, a trained reserve of 750 thousand people was formed. It is easy to see that formally this was not a reduction in the terms of service, but only the provision of temporary "leave" to the soldiers - a deception, so to speak, for the good of the cause.

JUNKER AND MILITARY REGIONS

No less acute was the issue of officer training. Back in 1840, Milyutin wrote:

“Our officers are shaped just like parrots. Until they are produced, they are kept in a cage, and they constantly tell them: "Ass, to the left around!", And the ass repeats: "To the left around." When the ass reaches the point that he firmly memorizes all these words and, moreover, will be able to stay on one paw ... they put on epaulettes for him, open the cage, and he flies out of it with joy, with hatred for his cage and his former mentors.

In the mid-1860s, at the request of Milyutin, military educational institutions were transferred to the subordination of the War Ministry. The cadet corps, renamed military gymnasiums, became secondary specialized educational institutions. Their graduates entered military schools, which trained about 600 officers annually. This turned out to be clearly not enough to replenish the command staff of the army, and it was decided to create cadet schools, upon admission to which knowledge was required in the amount of about four classes of an ordinary gymnasium. Such schools produced about 1,500 more officers a year. Higher military education was represented by the Artillery, Engineering and Military Law Academies, as well as the Academy of the General Staff (formerly the Imperial Military Academy).

Based on the new charter on combat infantry service, published in the mid-1860s, the training of soldiers also changed. Milyutin revived the Suvorov principle - to pay attention only to what the privates really need to carry out their service: physical and drill training, shooting and tactical tricks. In order to spread literacy among the rank and file, soldier schools were organized, regimental and company libraries were created, and special periodicals appeared - “Soldier's Conversation” and “Reading for Soldiers”.

Talk about the need to re-equip the infantry has been going on since the late 1850s. At first, it was about remaking old guns in a new way, and only 10 years later, at the end of the 1860s, it was decided to give preference to the Berdan No. 2 rifle.

A little earlier, according to the "Regulations" of 1864, Russia was divided into 15 military districts. The departments of the districts (artillery, engineering, quartermaster and medical) were subordinate, on the one hand, to the head of the district, and on the other hand, to the corresponding main departments of the Military Ministry. This system eliminated excessive centralization of command and control, provided operational leadership on the ground and the possibility of rapid mobilization of the armed forces.

The next urgent step in the reorganization of the army was to be the introduction of universal conscription, as well as enhanced training of officers and an increase in the cost of material support for the army.

However, after Dmitry Karakozov shot at the monarch on April 4, 1866, the positions of the conservatives were noticeably strengthened. However, it was not only an attempt on the king. It must be borne in mind that each decision to reorganize the armed forces required a number of innovations. Thus, the creation of military districts entailed the “Regulations on the establishment of quartermaster warehouses”, “Regulations on the management of local troops”, “Regulations on the organization of fortress artillery”, “Regulations on the management of the cavalry inspector general”, “Regulations on the organization of artillery parks” and etc. And each such change inevitably aggravated the struggle of the minister-reformer with his opponents.

MILITARY MINISTERS OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE

A.A. Arakcheev

M.B. Barclay de Tolly

From the moment the Military Ministry of the Russian Empire was created in 1802 until the overthrow of the autocracy in February 1917, this department was headed by 19 people, including such notable figures as Alexei Arakcheev, Mikhail Barclay de Tolly and Dmitry Milyutin.

The latter held the post of minister for the longest time - as much as 20 years, from 1861 to 1881. Least of all - from January 3 to March 1, 1917 - the last war minister of tsarist Russia, Mikhail Belyaev, was in this position.

YES. Milyutin

M.A. Belyaev

BATTLE FOR UNIVERSAL MILITARY

Not surprisingly, since the end of 1866, the rumor about Milyutin's resignation has become the most popular and discussed. He was accused of destroying the army, glorious for its victories, of democratizing its order, which led to a fall in the authority of officers and to anarchy, and of colossal spending on the military department. It should be noted that the ministry's budget was actually exceeded by 35.5 million rubles only in 1863. However, Milyutin's opponents proposed cutting the amounts allocated to the military department so much that it would be necessary to cut the armed forces by half, stopping recruiting altogether. In response, the minister presented calculations from which it followed that France spends 183 rubles a year on each soldier, Prussia - 80, and Russia - 75 rubles. In other words, the Russian army turned out to be the cheapest of all the armies of the great powers.

The most important battles for Milyutin unfolded in late 1872 - early 1873, when a draft Charter on universal military service was being discussed. At the head of the opponents of this crown of military reforms were Field Marshals Alexander Baryatinsky and Fyodor Berg, the Minister of Public Education, and since 1882 the Minister of the Interior Dmitry Tolstoy, Grand Dukes Mikhail Nikolayevich and Nikolai Nikolayevich the Elder, Generals Rostislav Fadeev and Mikhail Chernyaev and chief of gendarmes Pyotr Shuvalov. And behind them loomed the figure of the ambassador to St. Petersburg of the newly created German Empire, Heinrich Reuss, who received instructions personally from Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The antagonists of the reforms, having obtained permission to get acquainted with the papers of the Ministry of War, regularly wrote notes full of lies, which immediately appeared in the newspapers.

All-class military service. Jews in one of the military presences in the west of Russia. Engraving by A. Zubchaninov from a drawing by G. Broling

The emperor in these battles took a wait-and-see attitude, not daring to take either side. He either established a commission to find ways to reduce military spending chaired by Baryatinsky and supported the idea of replacing the military districts with 14 armies, then he leaned in favor of Milyutin, who argued that it was necessary either to cancel everything that was done in the army in the 1860s, or to go firmly to end. Naval Minister Nikolai Krabbe told how the discussion of the issue of universal military service took place in the State Council:

“Today Dmitry Alekseevich was unrecognizable. He did not expect attacks, but he himself rushed at the enemy, so much so that it was terribly alien ... Teeth in the throat and through the spine. Quite a lion. Our old men left, frightened.”

DURING THE MILITARY REFORMS, IT IS POSSIBLE TO CREATE A COMPLETE ARMY MANAGEMENT AND TRAINING OF THE OFFICER CORPS, to establish a new principle of its recruitment, to re-equip the infantry and artillery

Finally, on January 1, 1874, the Charter on all-class military service was approved, and in the highest rescript addressed to the Minister of War it is said:

“With your hard work in this matter and with an enlightened look at it, you have rendered a service to the state, which I take great pleasure in witnessing and for which I express my sincere gratitude to you.”

Thus, in the course of military reforms, it was possible to create a coherent system of command and control of the army and training of the officer corps, establish a new principle for its recruitment, largely revive the Suvorov methods of tactical training of soldiers and officers, raise their cultural level, re-equip the infantry and artillery.

TEST BY WAR

The Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878 Milyutin and his antagonists met with completely opposite feelings. The Minister was worried, because the reform of the army was only gaining momentum and there was still much to be done. And his opponents hoped that the war would reveal the failure of the reform and force the monarch to heed their words.

In general, the events in the Balkans confirmed Milyutin's correctness: the army withstood the test of war with honor. For the minister himself, the siege of Plevna, or rather, what happened after the third unsuccessful assault on the fortress on August 30, 1877, became a real test of strength. The commander-in-chief of the Danube army, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich the Elder, shocked by the failure, decided to lift the siege from Plevna - a key point of Turkish defense in Northern Bulgaria - and withdraw troops beyond the Danube.

Presentation of the captive Osman Pasha to Alexander II in Plevna. Hood. N. Dmitriev-Orenburgsky. 1887. Minister D.A. Milyutin (far right)

Milyutin objected to such a step, explaining that reinforcements should soon come to the Russian army, and the position of the Turks in Plevna was far from brilliant. But the Grand Duke irritably answered his objections:

"If you think it possible, then take command over yourself, and I ask you to fire me."

It is difficult to say how events would have developed further if Alexander II had not been present at the theater of operations. He listened to the arguments of the minister, and after the siege organized by the hero of Sevastopol, General Eduard Totleben, on November 28, 1877, Plevna fell. Turning to the retinue, the sovereign then announced:

“Know, gentlemen, that today and the fact that we are here, we owe to Dmitry Alekseevich: he alone at the military council after August 30 insisted not to retreat from Plevna.”

The Minister of War was awarded the Order of St. George II degree, which was an exceptional case, since he did not have either the III or IV degree of this order. Milyutin was elevated to the dignity of a count, but the most important thing was that after the Berlin Congress, which was tragic for Russia, he became not only one of the ministers closest to the tsar, but also the de facto head of the foreign affairs department. From now on, Comrade (Deputy) Minister of Foreign Affairs Nikolai Girs agreed with him on all fundamental issues. Bismarck, an old enemy of our hero, wrote to the Emperor of Germany Wilhelm I:

"The minister who now has a decisive influence on Alexander II is Milyutin."

The Emperor of Germany even asked his Russian colleague to remove Milyutin from the post of Minister of War. Alexander replied that he would gladly fulfill the request, but at the same time he would appoint Dmitry Alekseevich to the post of head of the Foreign Ministry. Berlin hastened to withdraw its offer. At the end of 1879, Milyutin took an active part in the negotiations on the conclusion of the "Union of the Three Emperors" (Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany). The Minister of War advocated an active policy of the Russian Empire in Central Asia, advised to switch from supporting Alexander Battenberg in Bulgaria, preferring the Montenegrin Bozhidar Petrovich.

ZAKHAROVA L.G. Dmitry Alekseevich Milyutin, his time and his memoirs // Milyutin D.A. Memories. 1816–1843 M., 1997.

***

Petelin V.V. Life of Count Dmitry Milyutin. M., 2011.

AFTER REFORM

At the same time, in 1879, Milyutin boldly stated: "It is impossible not to admit that our entire state system requires a radical reform from top to bottom." He strongly supported the actions of Mikhail Loris-Melikov (by the way, it was Milyutin who proposed the general’s candidacy for the post of All-Russian dictator), which provided for a reduction in the redemption payments of peasants, the abolition of the Third Branch, the expansion of the competence of zemstvos and city dumas, and the establishment of general representation in the highest authorities. However, the time for reform was coming to an end. On March 8, 1881, a week after the assassination of the emperor by Narodnaya Volya, Milyutin gave the last battle to the conservatives who opposed the “constitutional” Loris-Melikov project approved by Alexander II. And he lost this battle: according to Alexander III, the country needed not reforms, but reassurance ...

“It IS IMPOSSIBLE NOT TO RECOGNIZE that our entire state system requires a radical reform from top to bottom”

On May 21 of the same year, Milyutin resigned, having rejected the offer of the new monarch to become governor in the Caucasus. The following entry appeared in his diary:

“In the present course of affairs, with the current leaders in the highest government, my position in St. Petersburg, even as a simple, unrequited witness, would be unbearable and humiliating.”

Upon retirement, Dmitry Alekseevich received as a gift portraits of Alexander II and Alexander III, showered with diamonds, and in 1904 - the same portraits of Nicholas I and Nicholas II. Milyutin was awarded all Russian orders, including the diamond signs of the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called, and in 1898, during the celebrations in honor of the opening of the monument to Alexander II in Moscow, he was promoted to field marshal general. Living in the Crimea, in the Simeiz estate, he remained true to the old motto:

“There is no need to rest without doing anything. You just need to change jobs, and that’s enough.”

In Simeiz, Dmitry Alekseevich streamlined the diary entries that he kept from 1873 to 1899, wrote wonderful multi-volume memoirs. He closely followed the progress of the Russo-Japanese War and the events of the First Russian Revolution.

He lived for a long time. Fate supposedly rewarded him for not giving his brothers enough, because Alexei Alekseevich Milyutin passed away 10 years old, Vladimir - at 29, Nikolai - at 53, Boris - at 55. Dmitry Alekseevich died in the Crimea at the age of 96, three days after the death of his wife. He was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow next to his brother Nikolai. In the Soviet years, the burial place of the last field marshal of the empire was lost ...

Dmitry Milyutin left almost all his fortune to the army, handed over a rich library to his native Military Academy, and bequeathed an estate in the Crimea to the Russian Red Cross.

ctrl Enter

Noticed osh s bku Highlight text and click Ctrl+Enter

Ksenia Belousenko.

Boris Petrovich Sheremetev

The history of the Belgorod region and Belgorod itself is closely connected with the name of Count Boris Petrovich Sheremetev, whose birth marks 360 years.

He was born in 1652 in Moscow, in an old boyar family of Pyotr Vasilyevich Sheremetev and Anna Fedorovna Volynskaya. At the age of 13 he was appointed to the room steward, which ensured closeness to the king and gave broad prospects for promotion in ranks and positions. According to some reports, Boris Sheremetev studied at the Kyiv Collegium (later the Academy), located in the Kyiv Lavra, and at the court of Peter I had a reputation as the most polite and most cultured person.

He tried not to interfere in any internal strife, but during the period of struggle between Peter and Princess Sophia, Boris Petrovich was one of the first among the boyars to appear to Peter Alekseevich and since then became his associate, although a certain distance between them has always been maintained. This was explained not only by the age difference - Sheremetev was 20 years older than the tsar, but also by Boris Petrovich's adherence to the old Moscow moral principles (although he also knew European etiquette), his wary attitude towards the "rootless upstarts" surrounded by Peter.

Winner

In 1687, Boris Petrovich received command of the troops in Belgorod and Sevsk, responsible for protecting the southern borders from Tatar raids. He already had experience in dealing with them, since in 1681 he became the Tambov governor and guarded the eastern part of the Belgorod border line. Although the governors of the Belgorod regiment were called Belgorod, in fact, the place of their stay since 1680 was Kursk, where the voivodship office was located.

In the service, he showed personal courage and skill in military affairs, "hitting the enemy repeatedly and putting him to flight at his very approach." In 1689 Sheremetev participated in a campaign against the Crimean Tatars. His border service lasted eight years.

In 1697-1699, Boris Petrovich went on a diplomatic mission to Europe - he visited Poland, Austria, Italy and was received everywhere with royal honors. However, his ties with the Belgorod region were not interrupted.

As a military leader and commander, Sheremetev gained historical fame during the Great Northern War (1700–1721). After the brutal defeat of the Russian troops near Narva, it was Sheremetev who brought Russia the first victory over the Swedes in the battle near the village of Erestfer, for which he was awarded the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called and promoted to field marshal. In 1702, Sheremetev defeated the Swedes at Hummelshof, in 1703 he took the cities of Wolmar, Marienburg and Noteburg, and a year later - Dorpat.

He was the first in Russia granted the title of count - for the suppression of the rebellion of the archers in Astrakhan in 1705-1706.

Borisovka owner

It was in 1705 that the count and field marshal became the owner of the Borisovka settlement, the name of which, as was believed for a long time, came from the name of the famous commander. However, Borisov local historians managed to find out that the settlement was called Borisovka even before Sheremetev entered into the rights of the owner. In 1695, the colonel, commander of the Belgorod residential regiment Mikhail Yakovlevich Kobelev became the owner of the village of Kurbatovo. On the site of the village and around it, the Borisovka settlement was formed after 1695. Why she began to bear such a name is still, unfortunately, unknown.

M. Ya. Kobelev was forced to “cede” his manor lands to Boris Petrovich Sheremetev, since nine serfs who fled from Sheremetev’s estates “with their wives, children and grandchildren” lived with him, Kobelev, for seventeen years. The reception of runaway serfs was considered a serious crime. For each year the fugitive lives with the landowner who accepted him, the latter must pay the old owner, in accordance with the "Cathedral Code", 10 rubles of the so-called "elderly and working money." So, M. Ya. Kobelev had to pay Sheremetev a huge amount for those times.

Reading a large number of documents on the land acquisitions of the Sheremetevs, you come to the conclusion how far from real life the legend that the Borisov lands were “donated” by Peter I to his field marshal “to the horizon”, visible from the high Monastery Mountain. In reality, there was a massive ruin of petty service people, a massive buying up of their estates, due to which large estates of Peter's close associates were formed.

But the Tikhvin Convent was indeed founded by Boris Petrovich (pictured). He especially honored the icon of the Mother of God of Tikhvin: she accompanied him on all campaigns.

By the day of the Battle of Poltava (June 27, 1709), which turned the tide of the war with Sweden, Peter, leaving himself the overall leadership of the battle, appointed Sheremetev commander in chief. “Mr. Field Marshal,” the Tsar then said, “I entrust my army to you and I hope that in commanding it you will act according to the instructions given to you, and in case of an unforeseen event, like a skilled commander.” In the battle, which turned out to be "very fleeting and successful," Boris Petrovich actually led the actions of the center of the Russian troops.

Going to the battle of Poltava, he vowed to build a monastery in honor of his beloved icon in case of victory, placing a small copper image of Tikhvin on his chest before the battle.

The general battle with the Swedes was appointed by Peter I on June 26. Coincidentally, it was on this day that the miraculous Tikhvin Icon was celebrated. The pious field marshal persuaded the sovereign to postpone the battle for one day in order to honor the holiday with a solemn service and ask for the protection and intercession of the Mother of God for the Russian army. The authority of Sheremetev was such that the tsar obeyed his field marshal. A day later, commanding the center of the Russian army, Sheremetev distinguished himself with unparalleled courage: being under fierce fire, he remained unharmed even when a bullet, breaking through armor and dress, touched his shirt - the Tikhvin icon on his chest protected him from death.

Returning after the victory from near Poltava, Peter I stopped by his colleague and friend at the Borisovka estate and stayed there for six weeks. It was here that Sheremetev told the sovereign his heartfelt desire to build a convent. The legend says that Peter I himself chose the place for the future monastery. Surveying the surroundings, he drew attention to the mountain above the Vorskla River, ordered to make a large wooden cross and hoisted it on top with his own hand, thereby appointing a place for building the future Transfiguration Church. The main church, already by the will of Count Sheremetev, was built in the name of the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God, and the monastery received the name Bogoroditsko-Tikhvin. The field marshal presented the monastery with the “standard” Tikhvin icon, the same one that accompanied him in the Poltava battle. By 1713, a church, a bell tower, and cellars, and “svetlitsy” were built for the nuns, monastic gardens with apple, pear, and plum trees were laid out.

In 1923 the monastery was blown up. Today, on the streets of Borisovka, there remains the building of the former almshouse, occupied until recently by a boarding school, and several residential premises in which the nuns lived.

In 2000, at the invitation of the governor E. Savchenko, Pyotr Petrovich Sheremetev, a direct descendant of Boris Petrovich, visited the Belgorod region for the first time. He visited Belgorod and Stary Oskol, Alekseevsky, Yakovlevsky, Prokhorovsky and Borisovsky districts. In the Forest on Vorskla reserve, Petr Petrovich was shown ancient oaks that are more than three hundred years old, and they may remember Peter I and Boris Sheremetev, who rested here after the Battle of Poltava. And Peter Petrovich got even more excited when the priest of the Mikhailovsky Church in Borisovka showed him the icon of the Tikhvin Mother of God, who during the Poltava battle saved his illustrious ancestor. The bullet hole is still visible today.

In the memory of the people

But back to the biography of Boris Petrovich. During the Prut campaign of 1711, he led the main forces of the Russian army. Then he was sent to conclude a peace treaty with the Turks. Upon returning from Constantinople, Boris Petrovich took part in campaigns in Pomerania and Mecklenburg. After numerous strenuous campaigns, the 60-year-old field marshal felt tired. He wanted to find solitude and peace, intending to take the veil as a monk of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra. However, Peter I judged differently, marrying Sheremetev to a young widow, Anna Petrovna Naryshkina, nee Saltykova. They had five children from this marriage. The last child, daughter Ekaterina, was born on November 2, 1718 - three and a half months before the death of the field marshal. From the first wife, Evdokia Alekseevna Chirikova, there was a daughter and two sons.

According to the memoirs of contemporaries, “Count Boris Petrovich ... was tall, had an attractive appearance, strong body build. He was distinguished by his piety, ardent love for the throne, courage, strict performance of duties, generosity.

He devoted the last years of his life to charity. ... Widows with children, deprived of hope of food, and weak old men who lost their sight, received all kinds of benefits from him.

A supporter of the reforms of Peter I, Sheremetev, however, sympathized with Tsarevich Alexei and did not participate in his trial, citing illness. According to doctors, the field marshal suffered from dropsy, which took on severe forms. He died at the age of 67 in Moscow.

Shortly before his death (February 17, 1719), Boris Petrovich made a will in which he expressed his desire to be buried in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra. But the tsar believed that the first Russian general-field marshal should be buried in St. Petersburg, in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, where the graves of prominent statesmen and members of the royal family would be located. The ashes of Sheremetev were delivered to the new capital of Russia, and a solemn funeral was arranged for him. Peter I himself walked behind the coffin of Boris Petrovich.

In the Belgorod region, the memory of Boris Petrovich Sheremetev, governor of the Great Belgorod Regiment, military figure, diplomat, associate of the great reformer tsar, "the chick of Petrov's nest" is honored. In 2009, on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Battle of Poltava, a monument to the famous commander was erected in the center of Borisovka (sculptor A. Shishkov). In March 2011, the Sheremetev Musical Assemblies festival was held in Belgorod, and the chairman of the Russian Musical Society in France, the rector of the Russian Conservatory in Paris, Count Pyotr Petrovich Sheremetev, was invited as a guest of honor.

The highest military rank in the ground forces of the German, Austrian and Russian armies. First introduced in Germany in the 16th century. In Russia, it was introduced in 1699 by Peter I. In France and some other states, it corresponded to a military rank ... ... Wikipedia

General Field Marshal, Privy Councillor, b. On April 25, 1652, he died on February 17, 1719. Boris Petrovich was the eldest of the sons of the boyar Pyotr Vasilyevich Sheremetev (Bolshoy) and until the age of 18 he lived with his father, mainly in Kyiv, where he visited the Old ...

- (German Feldmarschall), or General Field Marshal (German Generalfeldmarschall) is the highest military rank that existed in the armies of the German states, the Russian Empire, the Holy Roman Empire and the Austrian Empire. Corresponds to ... ... Wikipedia

Lieutenant General ... Wikipedia

A position in the central (commissariat) military administration of the Russian army, literally the chief military commissioner (meaning for supply). The general krieg commissar was in charge of supply issues, clothing and monetary allowances for personnel and ... Wikipedia

This term has other meanings, see General Admiral (meanings). General admiral is one of the highest military ranks in the fleets of a number of states. Contents 1 Russia 2 Germany 3 Sweden ... Wikipedia

Field shoulder strap Major General of the Russian Ground Forces since 2010 Major General is the primary military rank of the highest officer, located between a colonel or brigadier general and ... Wikipedia

- ... Wikipedia

Field Marshal; son of a room steward, Prince. Vladimir Mikhailovich Dolgorukov, born in 1667. At first he served as a steward, and then moved to the Preobrazhensky Regiment. In the rank of captain, in 1705, he was wounded during the capture of the Mitava castle, in ... ... Big biographical encyclopedia

Order "For military valor" [[File:| ]] Original name Virtuti Militari Motto "Sovereign and Fatherland" Country Russia, Poland Type ... Wikipedia

Books

- No wonder the whole of Russia remembers... Gift edition (number of volumes: 3), Ivchenko L. For the 200th anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812, "Young Guard" has prepared many new editions. Among them are the biographies of the commanders who survived the battles with the previously invincible Napoleon and ...

- Tsesarevna. Sovereigns of Great Russia, Krasnov Pyotr Nikolaevich. Lieutenant General, Ataman of the Don Army P. N. Krasnov is also known as a writer. The novel "Tsesarevna" depicts Russia during the reign of Anna Ioannovna, then Anna Leopoldovna and Elizabeth ...