What is death or we all die. The science of death: what do we know about the last seconds of life and what happens after

- The taboo on talking about death is one of the strongest in modern society.

- Death is more frightening for those who have not become themselves.

- The realization that life is finite helps us to live fuller, deeper, richer.

Death - someone else's, and even more so one's own - belongs to the realm of the inexpressible. We ignore it, avoid it, deny it. But in order to live more meaningfully and vividly, we have to learn to think about it without fear.

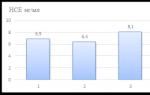

“I can’t imagine how you will write about it. It is so hard!" - the psychotherapist Inna Khamitova told me when we met to talk about death and how we relate to it. And I felt something inside me shrink into a ball in response. Neither the sun nor death can be looked at point-blank, said La Rochefoucauld*. It is not surprising that the editorial assignment aroused great anxiety in me: for a long time I avoided not only talking, but even thinking about death, about incurable diseases, about catastrophes that entailed human casualties. Many people do this - at best, we symbolically pay off death by sending money for an operation to a seriously ill person or to support a hospice, and on this we close the topic for ourselves. A Psychologies poll found that 57% of us rarely think about it. And even the bravest among us are not free from fear. “This dark shadow is something no living being can get rid of,” writes psychotherapist Irvin Yalom**. But if it frightens us so much, is it necessary to talk about it?

Children's questions

There are many paradoxes in the subject of death. The beginning of a new life is at the same time the first step towards the end. The consciousness of its inevitability should deprive our life of meaning, and yet it does not prevent us from loving, dreaming, and rejoicing. The question is how we try to resolve for ourselves or at least comprehend these contradictions. Most of the time, our thoughts fail. “We always have a few suitable maxims in reserve, with which we are ready to regale others on occasion,” wrote Carl Gustav Jung, the founder of analytical therapy, “Everyone must die sometime,” “Human life is not eternal” ***. Using a suitable stamp as a lifeline, we live as if we were immortal.

The origins of our relationship to death lie in childhood experience. “At a very early age, a child has no concept of time or cause-and-effect relationships, and, of course, there is no fear of death,” explains Inna Khamitova. “But already at the age of four, he can understand that someone close to him has died. Although he does not realize that this is leaving forever. It is very important how parents behave at this moment, the psychotherapist emphasizes. For example, many adults do not take children to funerals so as not to scare them ... and in vain. In fact, it is scary just for adults, and they involuntarily broadcast their fear to the child, attributing their attitude to death to him. Silence on this topic also affects children in the same way. The child reads the message: we don't talk about it, it's too scary. Thus, a painful, neurotic attitude towards death can arise. Conversely, if some rituals are observed in the family, for example, they remember the deceased grandmother on her birthday, this helps children cope with fear.

At first, children are afraid of the death of their parents and other loved ones. The child also knows about his mortality, but he realizes it only later - closer to adolescence. “Adolescents have an increased interest in death,” notes Inna Khamitova. – For them, this is a way to understand themselves, to feel their boundaries, to feel alive. And at the same time a way to switch the alarm. They seem to prove to themselves: I am not afraid, death is my sister.

Over the years, this fear recedes before the main life tasks of young adults: to master a profession, to start a family. “But three decades later ... a midlife crisis breaks out, and the fear of death falls on us with renewed vigor,” recalls Irvin Yalom. – Reaching the pinnacle of life, we look at the path in front of us and understand that now this path does not lead up, but down, to sunset and disappearance. From this moment on, anxiety about death does not leave us anymore.

Death as an art object

In any art museum in the world, an inexperienced visitor (especially a child) is struck by the ubiquitous presence of martyrdom, violence, and death. What is at least repeatedly repeated and invariably frightening head of John the Baptist on a platter. Contemporary art also explores the eternal story, forcing you to literally try on the process of dying. Two years ago in Paris, in the Louvre at the First Salon of Death, the visitor could lie down in one of the coffins on display and pick up a suitable copy for the future. This spring, the Moscow Manege hosted the exhibition Reflecting on Death, followed by the art project My Most Important Suitcase, in which participants were asked to pack their luggage for their “last journey”. Someone put toys in it, someone put an open laptop, a manifesto of their own composition... An imaginary death becomes an occasion to think about life, about its main values. Art critics see this as a new trend: an attempt to overcome the taboo on talking about death. Although it is more accurate to speak only about the modern forms of this overcoming - after all, art, along with religion, has always offered us to look into the face of death and not look away. It “awakens in us feelings that we might experience in a similar situation,” says Inna Khamitova. “For us, this is a way to touch the topic and live it, process it in a safe way.”

Eyes wide shut

“Today, only in small towns or in the countryside, the tradition of burying the whole world is preserved. Children are present at the funeral, they hear the conversations of adults - that one has died, or this one will die soon, and perceive death as a natural thing, part of the eternal cycle, says Jungian analyst Stanislav Raevsky. “And in the big city, there seems to be no death, it is banished from sight. Here you will no longer see a funeral in the yard, you will not hear a funeral orchestra, as it was 25-30 years ago. We see death closely when someone close to us dies. That is, we can not face it for many years. Interestingly, this is offset by the abundance of deaths that we see on TV, not to mention computer games, where the hero has many lives. But this is an emasculated, artificial, constructed death, which in our fantasies seems to be under the control of our power.

Repressed fear breaks through the way we speak. “I’m dying - I want to sleep”, “you will drive me into a coffin”, “tired to death” - our speech is sprinkled with references to death, although we do not mean it at all. But the “real” death in our language remains taboo - we prefer to speak in a sublime style (“passed away”, “left this world”, “ended his days”, “fell eternal sleep”) or, conversely, deliberately dismissively (“ gave up”, “played in the box”, “gave the oak”) - just not to call a spade a spade. And yet, sometimes we involuntarily become aware of this fear, says Inna Khamitova: “Funerals, serious illnesses, accidents, any partings bring us back to thoughts of death and the fears associated with it.”

What are we really afraid of?

“At the very bottom of our feelings about death lies a purely biological fear, at the level of instinct,” admits Irvin Yalom. “It's a primal fear, and I've experienced it too. Words cannot express it."

But unlike other living beings, man knows that someday he will die. From this follow fears of a higher order, and above all - the fear of non-existence (for believers - other-being), which we cannot comprehend. About this "after" - Hamlet's monologue: "To die. Sleep forget. Fall asleep... and dream? Here is the answer. What dreams will be dreamed in that mortal dream, When the veil of earthly feeling is removed? The path to non-existence is all the more terrible because everyone will have to do it alone. As Irvin Yalom says: “In death, a person is always alone, more alone than ever in life. Death not only separates us from others, but also dooms us to a second, more frightening form of loneliness - separation from the world itself.

Finally, with each of us goes our unique inner world, which exists only in our minds. “The death of a person is perhaps even worse than physical death,” Inna Khamitova reflects. “In fact, we are afraid of disappearing. Such is the nature of the fear of infirmity, severe illness or dementia, which may precede death. It’s the fear of not being yourself, of losing your identity.”

Eros vs. Thanatos

According to psychoanalysis, in each of us the drive to life and the drive to death coexist and oppose (by the way, the discovery of the latter belongs to the Russian student Sabina Spielrein, a student of Carl Gustav Jung). The life instincts, called Eros, are expressed in the need for love, creation, serve to maintain vital processes and ensure the reproduction of the species. The most important among them, according to Freud*, are the sexual instincts (libido). Conversely, the death instincts, united under the name Thanatos, manifest themselves in aggressive feelings, destructive desires and actions. Freud considered them to be biologically determined and as important regulators of behavior as the life instincts. “The goal of all life is death,” he wrote, meaning that any living organism eventually inevitably returns to a state of inorganic matter. And the life path of a person is an arena of struggle between Eros and Thanatos. However, Freud himself called this just a hypothesis, and so far it remains one of the controversial aspects of his teaching.

* Z. Freud "Beyond the Pleasure Principle" (AST, Astrel, 2011).

How do we deal with it

“Learning to understand the death of other people, its action in them, its action in us through the experience of someone else’s death, we will be able to look death in the face, in the end - to face our own death - at first as a possibility, or rather an inevitability, but inevitability is often as if so far away that we do not reckon with it - and then as the very reality that is coming upon us, ”explains Metropolitan Anthony of Surozh ****. And yet, to the very end, we are afraid of this "face to face." Over the millennia, mankind has come up with many ways to alleviate the suffering caused by this fear. The most powerful of them is religion, which gives hope for eternal life, for reunion with those whom we loved and lost, for retribution for a righteous life (however, this hope gives rise to another fear - to always pay for your sins). We try to counter this fear by symbolically securing our immortality through our children or our accomplishments. The formula “build a house, plant a tree, raise a son” reinforces precisely this desire to leave a mark, not to be forgotten, to continue oneself even beyond the threshold of death.

Although, it would seem, what difference does it make to us whether we leave a trace or not, since we will still be gone? “The whole question is what we consider our “I”, says Stanislav Raevsky. Where do we draw the line between self and non-self? Is it just the boundaries of our body? Is my “I” only in my inner space?” There is an exercise that helps to cope with the fear of death, the Jungian analyst continues: “You need to go out, let’s say, into the street, look around and say to yourself: “This car is me! The flower is me! Heaven is me! And so, over and over again, the understanding is trained that our “I” is not only inside, but also outside. Yes, the inner dies, but the outer remains...

Last criterion

Our experts agree that the fear of death is the stronger, the less a person has managed to realize himself. “Older people who are satisfied with their lives and realize that they have done everything they could in it are much calmer about death,” notes Inna Khamitova. “And it’s completely different when a person realizes that he has not lived his life, when he is overwhelmed by regrets about missed opportunities.”

“What does a person think about before death? - continues Stanislav Raevsky. - About your finances, about your car? About the countries you wanted to visit but didn't manage to visit? No, he is much more concerned about the essential questions: did I really love other people? Have you thought about them? Have you forgiven your enemies? The more we love others, the less our attachment to ourselves, the less painful the subject of death for us. And what a pity that these questions arise too late. But what if you start asking yourself 40 years before your death?” However, in many countries there is such an opportunity. On a special slate board, everyone who wants to add the phrase: “Before I die, I want ...” ***** And there are as many different desires as those who write: to get married, swim across the English Channel, have a bald cat, have a threesome .. .

Death, if we remember it, becomes the measure of our life. That is why psychologists invite their clients to imagine that they do not have long to live - say, a year. What would they change in their lives? In fact, this is thinking about your values, priorities, about meaning. “We are thinking that it is time to do something real, something that we have always put off, what our soul called for. The feeling of the proximity of death makes us develop and live our lives more fully, interestingly, deeply, - says Stanislav Raevsky. “And vice versa, by avoiding thoughts of death, we cut off a large part of life from ourselves.”

Face your fears

An adult is trying to meet his fear and understand it. However, many of us choose to act like children, denying our fear by running away from it. “But what we avoid will still catch up with us. If we avoid the topic of death, our anxiety will only grow,” warns Stanislav Raevsky. It can manifest itself in nightmares or masquerade as another psychological problem. And for someone it develops into horror and poisons existence.

It seems like the only thing that makes sense is to face your fear. Does this mean that we will get rid of it? No, answers Irvin Yalom: “Confrontation with death will always be accompanied by fear. Such is the price of self-consciousness." And yet the game is worth the candle: “Having understood the conditions of human existence, we can not only fully enjoy every minute of life and appreciate the very fact of our existence, but also treat ourselves and other people with genuine compassion.”

* F. de La Rochefoucauld "Maxims" (AST, 2011).

** I. Yalom “Peering into the sun. Life without fear of death” (Eksmo, 2008).

*** C. G. Jung, The Problems of the Soul of Our Time (Progress, 1994).

**** A. Surozhsky "Life, disease, death" (Vinograd, 1998).

***** Now there are more than 300 such boards in 20 languages in 50 countries of the world. For more information about the Before I die project, visit beforeidie.cc

Extend your existence on the Internet, die, but stay online...

Why do we need blogs and pages of the dead, videos of funerals and announcements of deaths? Psychologist Veronika Nurkova comments.

Among the videos posted on YouTube, there are often videos of funerals. And not only famous people, but also those whom only relatives, friends and colleagues know. Why is there such an interest in the visual side of death on the Web, why flaunt footage of parting with the departed? “Photographs in this case are an artifact of life, evidence that life was and lived to the end,” says Veronika Nurkova. “Paradoxically, the dead are photographed in order to remember them alive.” Exactly the same impression - they want to remember him alive and prolong his existence - arises from viewing social media accounts that someone close continues to maintain after the death of the owner. “On the one hand, it is difficult to imagine a more organic memorial site: by analogy with how real commemorations are usually held in the house of the deceased, the virtual “house” becomes the place of his virtual commemoration,” the psychologist argues. - On the other hand, an account is thought of as part of an inheritance, and close people who know the password to it consider themselves entitled to use the legally obtained space. Finally, there are cases where someone maintains the account of the deceased in order to create the illusion that the life of the deceased continues. Here it is appropriate to talk about psychological protection through identification with the deceased.

However, the developers of the largest social networks have already come up with technical immortality for their users. So, Twitter created the LivesOn add-on, thanks to which the page of the deceased continues to be updated with new messages in the style and vocabulary of the deceased. A less infernal way of preserving memory is also practiced - memorial pages, where you can publish photos, memories and artifacts about the departed.

The network creates new life after death. Therefore, even the piercing diaries of the dying (and the dead) have hundreds of reposts and reconcile with the inevitability of the end. One notable example is Canadian Derek Miller's penmachine.com blog, in which the top post begins with the words: “Well, that's it. I'm dead and this is my last blog post. I have asked family and friends to publish this pre-written message,<...>which will be the first step in turning the current website into an archive.”

Another example of this genre is the one that gained fame on the Web. A visual, almost minute-by-minute experience of awareness of inevitable death and a dignified departure from life today is in demand by millions of visitors.

Perhaps the most shocking project is Internet sweepstakes like deathlist.net. Here, lists of those who “should” die in the current year are compiled, and then the correctly guessed deaths are counted. “It's like getting up early in the morning at the window and ordering the sun to rise,” says Veronika Nurkova. – Sites of this type are an attempt to feel control over death. It is noteworthy that in the top list all people are very old or sick: the high probability of the forecast gives its author the illusion of power.

Anastasia Askochenskaya

Memory is mortal

To begin with, I would like to try to dispel the attitude towards death that has developed in modern man: fear, rejection, the feeling that death is the worst thing that can happen to us, and we must strive with all our might to survive, even if survival bears very little resemblance to real life.

In ancient times, when Christians were closer both to their pagan roots and to the exciting, amazing experience of conversion, to the revelation in Christ and through Him of the Living God, death was spoken of as a birth into eternal life. Death was perceived not as an end, not as a final defeat, but as a beginning. Life was considered as a path to eternity, which could be entered through the opened gates of death. That is why the ancient Christians so often reminded each other of death with the words: have a memory of death; that is why in the prayers, which, as a precious heritage, John Chrysostom gave us, there are lines where we ask God to give us the memory of death. When a modern person hears this, he usually reacts with rejection, disgust. Do these words mean that we must remember: death, like the sword of Damocles, hangs over us by a thread, the celebration of life can end tragically, cruelly at any moment? Are they a reminder, with every joy we meet, that it will certainly pass? Do they mean that we seek to darken the light of each day with the fear of coming death?

This was not the feeling of Christians in antiquity. They perceived death as a decisive moment, when the time of doing on earth ends, and, therefore, it is necessary to hurry; we must hasten to accomplish on earth everything that is in our power. And the purpose of life, especially in the understanding of spiritual mentors, was to become the true person that we were conceived by God, to the best of our ability to approach what the Apostle Paul calls the fullness of Christ's growth, to become - perhaps more perfect - the undistorted image of God.

The Apostle Paul in one of the Epistles says that we should value time, because the days are evil. Indeed, does not time deceive us? Don't we spend the days of our lives as if we were hastily, carelessly writing a draft of life, which we will someday rewrite completely; as if we are only going to build, only saving up everything that will later make up beauty, harmony and meaning? We live like this from year to year, not doing in full, to the end, in perfection what we could do, because “there is still time”: we will finish this later; this can be done later; someday we'll write a clean copy. Years pass, we do nothing, not only because death comes and reaps us, but also because at every stage of life we become incapable of what we could do before. In mature years, we cannot realize a beautiful and full of content youth, and in old age we cannot show God and the world what we could be in the years of maturity. There is a time for every thing, but when the time is gone, some things can no longer be done.

I have repeatedly quoted the words of Victor Hugo, who says that there is fire in the eyes of a young man and there must be light in the eyes of an old man. The bright burning fades, it is time to shine, but when the time has come to be light, it is no longer possible to do what could have been done in the days of burning. Days are evil, time is deceitful. And when it is said that we must remember death, it is not said that we should be afraid of life; this is said so that we can live with all the tension that we could have if we realized that every moment is the only one for us, and every moment, every moment of our life should be perfect, should not be a recession, but top of the wave, not defeat, but victory. And when I talk about defeat and victory, I don't mean outward success or lack thereof. I mean the inner becoming, the growth, the ability to be perfect and complete with everything that we are at the moment.

The value of time

Think about what every moment of our life would be like if we knew that it could be the last, that this moment is given to us in order to achieve some kind of perfection, that the words that we utter are our last words, and therefore should express all beauty, all wisdom, all knowledge, but also, and above all, all the love that we have learned during our lives, whether it was short or long. How would we act in our mutual relations if the present moment was the only one at our disposal and if this moment had to express, embody all our love and care? We would live with intensity and depth otherwise inaccessible to us. And we rarely realize what the present moment is. We move from the past into the future and do not really and fully experience the present moment.

Dostoevsky in his diary tells about what happened to him when, sentenced to death, he stood before execution - how he stood and looked around him. How magnificent was the light, and how wonderful the air that he breathed, and how beautiful the world around, how precious every moment, while he was still alive, although on the verge of death. Oh, - he said at that moment, - if they gave me life, I would not lose a single moment of it ... Life was given, - and how much of it was lost!

If we were aware of this, how would we treat each other, and even ourselves? If I knew, if you knew that the person you are talking to is about to die, and that the sound of your voice, the content of your words, your movements, your attitude towards him, your intentions will be the last thing he perceives and carry it away into eternity - how attentively, how carefully, with what love we would act!.. Experience shows that in the face of death any resentment, bitterness, mutual rejection is erased. Death is too great next to what should be insignificant even on the scale of temporary life.

Thus, death, the thought of it, the memory of it is, as it were, the only thing that gives life the highest meaning. To live at the level of the demands of death means to live in such a way that death can come at any moment and meet us on the crest of the wave, and not on its decline, so that our last words are not empty and our last movement is not a frivolous gesture. Those of us who happen to live for a while with a dying person, with a person who, like us, was aware of the approach of death, probably understood what the presence of death can mean for mutual relationships. It means that every word should contain all the reverence, all the beauty, all the harmony and love that seemed to be sleeping in this relationship. It means that nothing is too small, because everything, no matter how small, can be an expression of love or its denial.

Personal memories: mother's death

But as a result, two things happened. One is that at no point was my mother or I myself walled up in lies, had to play, were not left without help. I have never needed to enter my mother's room with a smile that was a lie, or with untruthful words. At no point have we had to pretend that life is winning, that death, disease is receding, that the situation is better than it really is, when we both know that this is not true. At no point were we deprived of mutual support. There were times when my mother felt she needed help; then she called, I came, and we talked about her death, about my loneliness. She deeply loved life. A few days before her death, she said that she would be ready to suffer another 150 years, just to live. She loved the beauty of the coming spring; she treasured our relationship. She yearned for our separation: Oh, for the touch of a vanished hand and the sound of a voice that is still... the pain of separation was unbearable for me, then I came and we talked about it, and my mother supported me and consoled me about her death.Our relationship was deep and true, there were no lies in them, and therefore they could contain all the truth to the depth.

And besides, there was another side, which I have already mentioned. Because death stood nearby, because death could come at any moment, and then it would be too late to fix anything - everything had to express at any moment as perfectly and fully as possible the reverence and love that our relationship was full of. Only death can fill with greatness and meaning everything that seems to be small and insignificant. How you serve a cup of tea on a tray, how you move the pillows behind the back of the patient, how your voice sounds - all this can become an expression of the depth of the relationship. If a false note is sounded, if a crack appears, if something is not right, it must be corrected immediately, because there is no doubt that later it may be too late. And this again puts us before the face of the truth of life with such sharpness and clarity that nothing else can give.

Too late?

This is very important, because it leaves an imprint on our attitude towards death in general. Death can be a challenge, allowing us to grow to our fullest potential, constantly striving to be all we can be - with no hope of becoming better later if we don't try to do the right thing today. Again, Dostoevsky, speaking about hell in The Brothers Karamazov, says that hell can be expressed in two words: “Too late!” Only the memory of death can allow us to live in such a way that we never have to face this terrible word, the terrifying obvious: it's too late. It is too late to utter words that could be said, too late to make a movement that could express our relationship. This does not mean that nothing more can be done at all, but it will be done in a different way, at a high price, at the cost of greater mental anguish.

I would like to illustrate my words, explain them with an example. Some time ago, a man in his 80s came to me. He sought advice, because he could no longer endure the torment in which he had lived for sixty years. During the civil war in Russia, he killed his girlfriend. They loved each other passionately and were about to get married, but during a shootout, she suddenly leaned out, and he accidentally shot her. And for sixty years he could not find peace. He not only cut off a life that was infinitely dear to him, he cut off a life that flourished and was infinitely dear to the girl he loved. He told me that he prayed, asked for forgiveness from the Lord, went to confession, repented, received a prayer of permission and took communion - he did everything that the imagination suggested to him and those to whom he turned, but he never found peace. Overwhelmed with ardent compassion and sympathy, I said to him: “You turned to Christ, whom you did not kill, to priests whom you did not harm. Why didn't you ever think to reach out to the girl you killed?" He was amazed. Doesn't God give forgiveness? After all, only He alone can forgive the sins of people on earth ... Of course, this is so. But I told him that if the girl he killed forgives him, if she intercedes for him, then even God cannot pass by her forgiveness. I invited him to sit down after evening prayers and tell this girl about sixty years of mental suffering, about a devastated heart, about the torment he experienced, ask her forgiveness, and then ask him to also intercede for him and ask the Lord for peace to his heart if she forgives. He did so, and peace came ... What was not done on earth can be done. What has not been completed on earth can be healed later, but at the cost, perhaps, of many years of suffering and remorse, tears and anguish.

Death is separation from God

When we think of death, we cannot think of it unambiguously, either as triumph or as sorrow. The image that God gives us in the Bible, in the Gospels, is more complex. In short, God did not create us for death and destruction. He created us for eternal life. He called us to immortality - not only to the immortality of the resurrection, but also to immortality, which did not know death. Death came as a result of sin. It appeared because a person lost God, turned away from Him, began to look for ways where he could achieve everything besides God. Man himself tried to acquire the knowledge that could be acquired through communion with the knowledge and wisdom of God. Instead of living in close communion with God, man has chosen selfhood, independence. One French pastor in his writings gives, perhaps, a good image, saying that at the moment when a person turned away from God and began to look into the infinity lying in front of him, God disappeared for him, and since God is the only source of life, there is nothing for a person. had no choice but to die.

If we turn to the Bible, we can be struck by something related to the fate of mankind. Death came, but it did not immediately take hold of humanity. Whatever the length of life of the first great biblical generations in objective figures, we see that the number of their days is gradually decreasing. There is a place in the Bible where it is said that death conquered mankind gradually. Death came, although the power of life still remained; but from generation to generation of mortal and sinful people, death kept shortening human life. So there is tragedy in death. On the one hand, death is monstrous, death should not be. Death is a consequence of our loss of God. However, there is another side to death. Infinity in separation from God, thousands and thousands of years of life without any hope that this separation from God will come to an end - this would be worse than the destruction of our bodily composition and the end of this vicious circle.

There is another side to death: no matter how narrow its gates are, they are the only gates that allow us to escape the vicious circle of infinity in separation from God, from fullness, allowing us to escape from the created infinity, in which there is no space, in order to again become partakers of Divine life, in ultimately - partakers of the Divine nature. Therefore, the Apostle Paul could say: Life for me is Christ, death is gain, because, living in the body, I am separated from Christ ... That is why in another place he says that for him to die does not mean putting himself off, throwing off temporary life; for him to die is to put on eternity. Death is not the end, but the beginning. This door opens and lets us into the expanse of eternity, which would be forever closed to us if death did not release us from the slavery of the earth.

ambivalence

There must be both sides to our relationship to death. When a person dies, we can legitimately be brokenhearted. We can watch with horror that sin has killed the person we love. We may refuse to accept death as the last word, the last event of life. We are right when we weep over the deceased, because there should not be death. The man is killed by evil. On the other hand, we can rejoice for him, because a new life has begun for him (or for her), a life without limits, spacious. And again, we can cry over ourselves, over our loss, our loneliness, but at the same time we must learn that the Old Testament already sees clearly, predicts when it says: love is strong as death, love that does not allows the memory of a loved one to fade, a love that allows us to talk about our relationship with a loved one not in the past tense: “I loved him, we were so close”, but in the present: “I love him; we're so close." So there is complexity in death, one might even say duality; but if we are Christ's own people, we have no right, because we ourselves are deeply wounded by loss and orphaned in an earthly way, not to notice the birth of the deceased into eternal life. In death there is a force of life that reaches us.

If we admit that our love belongs to the past, this means that we do not believe that the life of the deceased has not ended. But then we have to admit that we are unbelievers, atheists in the crudest sense of the word, and then we have to look at the whole question from a completely different point of view: if there is no God, if there is no eternal life, then the death that has occurred has no metaphysical significance. It's just a natural fact. The laws of physics and chemistry won, man returned to the duration of being, to the cycle of natural elements - not as a person, but as a particle of nature. But in any case, we must honestly face our faith or lack of it, take a stand and act accordingly.

More personal memories

It is difficult, almost impossible, to talk about matters of life and death detachedly. So I will speak personally, perhaps more personally than some of you will like. In our lives, we encounter death primarily not as a topic for reflection (although this happens), but mostly as a result of the loss of loved ones - our own or someone else's. This indirect experience of death serves as the basis for our subsequent reflections on the inevitability of our own death and how we relate to it. Therefore, I will begin with a few examples of how I myself have met with the death of other people; perhaps this will explain to you my own attitude towards death.

My first recollection of death dates back to a very distant time, when I was in Persia as a child. One evening my parents took me with them to visit, as was customary then, the rose garden, famous for its beauty. We came, we were received by the owner of the house and his household. We were led through a magnificent garden, offered refreshments, and sent home with the feeling that we had received the warmest, most cordial, unfettered hospitality imaginable. Only the next day we learned that while we were walking with the owner of the house, admiring his flowers, were invited to a treat, were received with all the courtesy of the East, the son of the owner of the house, killed a few hours ago, was lying in one of the rooms. And this, small as I was, gave me a very strong sense of what life is and what death is, and what is the duty of the living towards living people, whatever the circumstances.

The second memory is a conversation during the Civil War or the end of the First World War between two girls; the brother of one, who was the bridegroom of the other, was killed. The news reached the bride; she came to her friend, his sister, and said: "Rejoice, your brother died heroically, fighting for the Motherland." This again showed me the greatness of the human soul, human courage, the ability to resist not only danger, suffering, life in all its diversity, all its complexity, but also death in its naked sharpness.

This again showed me the measure of life, showed me what life should be in relation to death: the ultimate challenge to learn to live (as my father told me another time) in such a way as to expect my own death, as a young man waits for his bride, to wait for death, as waiting for your beloved - waiting for the door to open.

And then (and this should be thought through much more deeply than I was able to do, but I experienced this very keenly in my heart during the past Passion Week), if Christ is the door that opens to eternity, He is our death. And this can even be confirmed by a passage from the Epistle to the Romans, which is read at baptism; it says that we plunged into the death of Christ in order to rise with Him. And another passage in the Epistle, which says that we bear in our body the deadness of Christ. He is death, and He is Life itself and Resurrection.

Father's death

And the last image: the death of my father. He was a quiet man, spoke little; we rarely talked. On Easter he became unwell, he lay down. I sat next to him, and for the first time in our lives, we spoke with complete openness. Not our words were significant, but there was an openness of mind and heart. The doors opened. The silence was full of the same openness and depth as the words. And then it was time for me to leave. I said goodbye to everyone in the room, except for my father, because I felt that, having met the way we met, we could no longer be apart. We didn't say goodbye. It was not even said “goodbye”, “see you”; we met - and it was a meeting forever. He died the same night. I was informed that my father had died; I returned from the hospital where I worked; I remember I went into his room and closed the door behind me. And I felt a quality and a depth of silence that was not just the absence of noise, the absence of sound. It was an essential silence, a silence that the French writer Georges Bernanos described in one novel as "a silence that is itself a presence." And I heard my own words: “And they say that there is death… What a lie!”

Co-presence with the dying

Dying is different. I remember a young soldier who left behind a wife, a child, a farm. He told me: “I will die today. I'm sorry to leave my wife, but there's nothing you can do about it. But I'm so scared to die alone." I told him that this would not happen: I would sit with him, and as long as he was able, he could open his eyes and see that I was there, or talk to me. And then he can take my hand and shake it from time to time to make sure I'm there. So we sat, and he left in peace. He was spared the loneliness at death.

On the other hand, sometimes God sends a lonely death to a person, but this is not abandonment, this is loneliness in God's presence, in the confidence that no one will break in recklessly, dramatically, will not bring longing, fear, despair into the soul, which is able to freely enter eternity .

My last example concerns a young man who was asked to spend the night at the bedside of an elderly woman who was dying. She had never believed in anything outside of the material world, and now she was leaving it. The young man came to her in the evening, she no longer responded to the outside world. He sat down by her bed and began to pray; he prayed as best he could, both in words of prayers and in prayerful silence, with a feeling of reverence, with compassion, but also in deep bewilderment. What happened to this woman as she entered a world that she had always denied, that she had never experienced? She belonged to the earth - how could she enter into heaven? And that's what he experienced, that's what he thought he caught, communicating with this old woman through compassion, in perplexity. At first, the dying woman lay quietly. Then, from her words, her exclamations, her movements, it became clear to him that she was seeing something; judging by her words, she saw dark creatures; the forces of evil crowded around her bed, swarming around her, claiming that she was theirs. They are closest to the earth because they are fallen creatures. And then suddenly she turned and said that she saw the light, that the darkness that pressed her from all sides, and the evil beings surrounding her, were gradually receding, and she saw light beings. And she called for mercy. She said, "I'm not yours, but save me!" A little later she said, "I see the light." And with these words - "I see the light" - she died.

I give these examples so that you can understand why my attitude towards death may seem biased, why I see glory in it, and not just grief and loss. I see grief and loss. The examples I have given you refer to sudden, unexpected death, death that comes like a thief in the night. Usually this doesn't happen. But if you come across such an experience, you will probably understand how it is possible, although there is burning pain and suffering in the heart, at the same time to rejoice, and how - we will talk about this later - it is possible to proclaim in the funeral service: Blessed is the way, the way you go today, soul, as if a resting place has been prepared for you ... and why earlier in the same service, as if on behalf of the deceased, using the words of the psalm, we say: My soul will live and praise Thee, Lord ...

Aging

More often than sudden death, we are faced with a long or short illness leading to death, and with old age, which gradually leads us either to the grave, or - depending on the point of view - to liberation: to the last meeting, to which each of us, consciously or not, aspires and rushes all his earthly life - to our meeting face to face with the Living God, with Eternal Life, with communion with Him. And this period of illness or growing old age must be met and understood creatively, meaningfully.

One of the tragedies of life, which brings great mental suffering and anguish, is to see how a loved one suffers, loses physical and mental abilities, seems to lose what was most valuable: a clear mind, a lively reaction, responsiveness to life, etc. So often we try to push it away, get around it. We close our eyes so as not to see, because we are afraid to see and foresee. And as a result, death comes and is sudden, in it is not only the fright of suddenness, which I mentioned earlier, but also the additional horror that it strikes us at the very core of our vulnerability, because pain, fear, horror grew, grew inside us, and we refused to give them a way out, refused to mature internally ourselves. And the blow is more painful, more destructive than with sudden death, because besides horror, besides the bitterness of loss, it comes with all self-reproach, self-condemnation for the fact that we did not do everything that could be done - we did not do it because of that it would make us become truthful, become honest, not hide from ourselves and from an aging or dying person, that death gradually opens the door, that this door will one day open wide, and the beloved will have to enter it without even looking back.

Every time we are faced with the slowly approaching loss of a loved one, it is very important to look it in the face from the very beginning - and do it quite calmly, as we look in the face of a person while he is alive and among us. For the thought of impending death is opposed by the reality of the living presence. We can always rely on this undeniable presence and at the same time see more and more clearly all aspects of the loss coming to us. It is this balance between the persuasiveness of reality and the fragility of thought that allows us to prepare ourselves for the death of people who are dear to us.

Life eternal

Of course, such a preparation, as I have already said, entails an attitude towards death that recognizes, on the one hand, its horror, the grief of loss, but at the same time realizes that death is the door that opens to eternal life. And it is very important to remove barriers, not to let fear build a wall between us and the dying. Otherwise, he is condemned to loneliness, abandonment, he has to fight death and everything that it represents for him, without any support and understanding; this wall does not allow us to do everything that we could do so that there is no bitterness left, no self-reproach, no despair. You cannot easily say to a person: “You know, you will die soon…” In order to be able to meet death, you need to know that you are rooted in eternity, not only to know theoretically, but to be experimentally sure that there is eternal life. Therefore, often, when the first signs of approaching death are visible, one must thoughtfully, persistently work to help the person who must enter into its secret, to discover what eternal life is, to what extent he already possesses this eternal life and how much confidence that that he possesses eternal life nullifies the fear of death - not grief of separation, not bitterness that death exists, namely fear. And some people can say: “Death is at the door; let's go together to her doorstep; let us grow together in this experience of dying. And let us enter together into that measure of communion with eternity, which is available to each of us.”

I would also like to illustrate this with an example. Thirty years ago, a man found himself in the hospital, as it seemed, with a mild illness. He was examined and found to have inoperable, incurable cancer. They told his sister and me, they didn't tell him. I visited him. He was lying in bed, strong, strong, full of life, and he told me: “How much more do I need to do in my life, and here I am, and they can’t even tell me how long it will last.” I answered him: “How many times have you told me that you dream of being able to stop time, so that you can be instead of doing. You never did. God did it for you. It's time for you to be." And in the face of the need to be, in a situation that could be called completely contemplative, he asked in bewilderment: “But how to do this?”

I pointed out to him that illness and death depend not only on physical causes, on bacteria and pathology, but also on everything that destroys our inner life force, on what can be called negative feelings and thoughts, on everything that undermines our inner life. the power of life in us, does not allow life to flow freely in a pure stream. And I suggested that he resolve not only externally, but also internally everything that in his relationships with people, with himself, with the circumstances of life was “not right”, starting from the present time; when he straightens everything in the present, go further and further into the past, reconciling with everything and everyone, untying every knot, remembering all evil, reconciling - through repentance, through acceptance, with gratitude, with everything that was in his life; but life was very hard. And so, month after month, day after day, we walked this path. He made peace with everything in his life. And I remember, at the very end of his life, he was lying in bed, too weak to hold a spoon himself, and he said to me with a beaming look: “My body is almost dead, but I have never felt so intensely alive as I do now.” He discovered that life depends not only on the body, that he is not only the body, although the body is he; discovered in himself something real that the death of the body could not destroy.

This is a very important experience that I wanted to remind you, because this is what we must do again and again, throughout our lives, if we want to feel the power of eternal life in ourselves and not be afraid, no matter what happens to temporary life, which also belongs to us.

From the book "Life. Disease. Death."

LENIN Vladimir Ilyich (pseudonym, real name Ulyanov) (1870-1924) - Russian revolutionary, eyes of the Communist Party and the first government of the USSR. In March 1922, Lenin began to have frequent seizures, consisting in a short-term loss of consciousness with numbness on the right side of the body.

From March 1923 severe paralysis of the right side of the body developed, speech was affected. Still, the doctors hoped to improve the situation. The bulletin on the state of Lenin's health dated March 22 said: "... This disease, judging by the course and the data of an objective study, is one of those in which an almost complete restoration of health is possible."

Indeed, when Lenin was transferred to Gorki in May, he began to recover. In September, orthopedists made special shoes for the leader; with the help of his wife and sister, he began to get up and walk around the room with a stick. In October, people with political messages were even allowed to see Lenin. OA Pyatnitsky, an employee of the Comintern, and I.I. Skvortsov-Stepanov, an employee of the Moscow Council, shared some political and economic news with the leader.

True, Lenin reacted to this with a single word that he pronounced tolerably: “just about.” And on October 19, Lenin accomplished a feat - against the persuasion of his wife, got into a car and ordered to be taken to Moscow. “I went to the apartment,” recalls Lenin’s secretary Fotiyev, - looked into the meeting room, went into his office, looked around everything, drove through the agricultural exhibition in the current Park of Culture and Recreation and returned to Gorki.

Gradually, Lenin began to learn to write with his left hand (the right was paralyzed). Things got to the point that many in the government and the Politburo expected Lenin to return to the leadership of the country soon. In December 1923, during a Christmas tree for children arranged in Gorki. Lenin spent the whole evening with the children.

But the will of the leader was powerless before the will of the disease. Cerebral sclerosis continued to turn off one part of the brain after another from activity.

In the last months of her life, Krupskaya, at the direction of Lenin, read fiction to him. Usually it was in the evening. I read Saltykov-Shchedrin, Gorky's My Universities, poems by Demyan Bedny. Two days before her death, Krupskaya, wanting to strengthen her husband's courage, read him Jack London's story "Love of Life". “Strong: a very thing,” she recalls of this reading. — Through the snowy desert, in which no human foot has set foot, a sick man dying of hunger makes his way to the pier of a large river. His strength is weakening, he does not walk, but crawls, and next to him crawls a wolf dying of hunger, there is a struggle between them, the man wins, half dead, half crazy gets to the goal. Ilyich liked this story extremely. The next day he asked me to read London's stories further... The next story was of a completely different type - saturated with bourgeois morality: some captain promised the owner of a ship loaded with bread to profitably sell it; he sacrifices his life just to keep his word. Ilyich laughed and waved his hand.

Well, one of the doctors who treated him, Professor V. Osipov, describes the last day of Lenin as follows:

“On January 20, Vladimir Ilyich experienced a general malaise, he had a poor appetite, a lethargic mood, there was no desire to study; he was put to bed, a light diet was prescribed. He was pointing at his eyes, obviously experiencing an unpleasant sensation in his eyes. Then an eye doctor, Professor Averbakh, was invited from Moscow, who examined his eyes ... The patient met Professor Averbakh very friendly and was pleased that when his vision was examined using wall tables, he could independently name letters aloud, which gave him great pleasure. Professor Averbakh most carefully examined the condition of the fundus of the eye and did not find anything painful there.

The next day, this state of lethargy continued, the patient remained in bed for about four hours, and Professor Foerster (a German professor from Breslau, who had been invited back in March 1922) and I went to Vladimir Ilyich to see what condition he was in.

We visited him in the morning, afternoon and evening, as needed. It turned out that the patient had an appetite, he wanted to eat; it was allowed to give him broth. At six o'clock the malaise increased, consciousness was lost, and convulsive movements appeared in the arms and legs, especially in the right side. The right limbs were tense to the point that it was impossible to bend the leg at the knee, cramps were also in the left side of the body. This attack was accompanied by a sharp increase in respiration and cardiac activity. The number of breaths rose to 36. and the number of heartbeats reached 120-130 per minute, and one very threatening symptom appeared, which is a violation of the correctness of the respiratory rhythm (such as a chain-stokes), this is a cerebral type of breathing, very dangerous, almost always indicating the approach of the fatal end. Of course, morphine, camphor, and whatever else might be needed was prepared. After some time, the breathing leveled off, the number of breaths dropped to 26, and the pulse to 90 and was of good filling. At this time we took the temperature - the thermometer showed 42.3 ۫ - a continuous convulsive state led to such a sharp increase in temperature; the mercury rose so much that there was no more room in the thermometer.

The convulsive state began to weaken, and we already began to harbor some hope that the seizure would end safely, but at exactly 6 o'clock. 50 min. suddenly there was a sharp rush of blood to the face, the face turned red to a crimson color, followed by a deep sigh and instant death. Artificial respiration was applied, which lasted 25 minutes, but it did not lead to any positive results. Death came from paralysis of breathing and heart, the centers of which are located in the medulla oblongata.

Once Lenin was shocked by the death of Paul and Laura Lafargue, who committed suicide. On December 3, 1911, he gave a speech at the funeral of the Lafargues at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Lenin, like Lafargue, believed that when a person cannot work for the benefit of the revolution (due to old age or illness), he must have the courage to voluntarily die.

There were rumors that Lenin was poisoned by Stalin - this, for example, was stated by Trotsky in one of his articles. In particular, he wrote: “During the second illness of Lenin, apparently in February 1923, Stalin, at a meeting of members of the Politburo (Zinoviev, Kamenev and the author of these lines), after the removal of the secretary, reported that Ilyich had summoned him unexpectedly to him and demanded to deliver him poison. He again lost the ability to speak, considered his situation hopeless, foresaw the proximity of a new blow, did not trust the doctors, whom he easily caught in contradictions, maintained complete clarity of thought and suffered unbearably ...

I remember how unusual, mysterious, inconsistent with the circumstances, Stalin's face seemed to me. The request he conveyed was of a tragic nature; There was a half-smile on his face, as if on a mask.

- Of course, there can be no question of fulfilling this request! I exclaimed...

“I told him all this,” Stalin objected, not without annoyance, “but he only brushes it off. The old man is suffering. He wants, he says, to have poison with him ... he will resort if he is convinced of the hopelessness of his situation.

Trotsky, however, says that Stalin could have invented that Lenin turned to him for poison in order to prepare his alibi. However, this episode is also confirmed by the testimony of one of Lenin's secretaries, who in the 60s told the writer A. Beck that Lenin really asked Stalin for poison. “When I asked doctors in Moscow,” Trotsky writes further, “about the immediate causes of death, which they did not expect, they vaguely shrugged their hands. of everything! But the doctors did not look for poison, even if the more perceptive ones admitted the possibility of suicide.

Most likely, Lenin did not receive poison from Stalin - otherwise Stalin would have subsequently destroyed all the secretaries and all the servants of Ilyich, so as not to leave traces, and Stalin did not have a special need for the death of an absolutely helpless Lenin. In addition, he has not yet approached the hell beyond which the physical destruction of his opponents began. Thus, the most likely cause of Lenin's death is illness.

Lenin's body, as you know, was embalmed and placed in a specially built mausoleum. Historian Lune Fischer says that when, in the 1930s, Western newspapers began to write that “in the mausoleum lies not an embalmed mummy, but a wax figure,” the Soviet authorities allowed a group of Western journalists (Fischer was one of them) to survey the shrine. The biochemist who embalmed Lenin, Professor B.I. Zbarsky, mentioned secret mummification processes to those gathered in the mausoleum and predicted that the body would remain in this form for a hundred years. "Then he opened the hermetically sealed glass case containing the relics, pinched Lenin's nose and turned his head right and left. It wasn't wax. It was Lenin."

What is death? How can a sane person pass by such a question indifferently and indifferently, when our earthly existence still remains an unsolved mystery by anyone? From the moment a person exists, his life begins with a cradle and ends with a coffin. It flows between two incomprehensible riddles: birth and death. When meeting a person coming into the world, we ask ourselves: “where and why?”, and seeing off - “why and where?”.

Indeed, it is impossible not to think about these two questions, if we remember that several billion human beings inhabiting the Earth and enjoying the blessings of life, within only one century, every single person, will lie down as lifeless corpses in the “mother earth”!

It is also impossible to remain indifferent to the sad, but irrefutable fact that death takes several tens of millions of human lives from the face of the earth every year. Every year more than one million tons of human meat, bones and blood falls into the ground, falls into the ground, like unnecessary garbage, to be there, decomposing into its original basic chemical elements.

Questions cannot but arouse our curiosity if we begin to think about the short duration and transience of our earthly life. Reflecting on this, King David said: “My heart was kindled in me, a fire was kindled in my thoughts, I began to speak with my tongue: tell me, Lord, my end and the number of my days, what is it, so that I know what my age is. Behold, You have given me days as spans, and my age as nothing before You. Truly, every living person is utter vanity. Indeed, a person walks like a ghost: in vain he fusses, collects and does not know who will get it ”... (Ps. 38th).

"Days like spans"!

"Span" is an old Russian measure of length, equal to the distance between the ends of the stretched fingers: thumb and index. With such an insignificant particle of space, David compared the days of our earthly existence.

How limited and short-lived is human life even in those cases when he reaches the utmost deep old age! Moses complains: “You return man to corruption and say: Return, sons of men! For a thousand years are before your eyes, like yesterday when it has passed, and like a watch in the night. You carry them away like a flood, they are like a dream - like grass that grows in the morning, blooms and turns green in the morning, is cut down and dries up in the evening ... we lose our summers, like a sound. The days of our years are 70 years, and with a greater fortress - 80 years, and their best time is work and illness, for they pass quickly and we fly ”... (Ps. 89th).

And, in fact, not having had time to sail from one bank of the river of life, as a fragile boat, ours is already ready to moor to its opposite bank. Doesn't it sometimes seem to us that we have been preparing for life for so long and diligently, and that life itself has turned out to be so short? Big and long fees for a short way!

Our life is short

Like a bird flying

And faster than the shuttle

Flies forward.

Our life is like a shadow

On earth we are given

And as soon as the sun goes down

She disappears.

Our life is like a sound

Like a hammer blow

Like an unexpected fear

So it's short...

Often, we do not even realize to what extent the time of our stay on earth is limited. “The days of our years are 70 years…”. Although many do not live to that age. But what do these 70 years of human life actually mean, if we subtract from them 1/3 (23 years) that we spend in a dream? Thus, out of 70 years, only 47 years will remain, from which 10 years of reckless childhood must be subtracted, and 10 years of study ... Only 27 years remain, during which a person needs to enter into work, marry, raise a family, provide for years of old age, to know oneself, the Universe surrounding one, to be reconciled with God, to form a God-pleasing character, to leave behind some noticeable trace of life, to determine one’s life purpose and eternal destiny…

But unfortunately, even this negligible amount of time that is given to a person, we sometimes spend aimlessly, senselessly and recklessly. Seneca said:

“People often complain about lack of time and don't know what to do with their time. Life is spent in idleness, laziness or doing things that don't matter. We say that the days of our life are not many, but we act as if there were no end to these days ... ".

Alas! Our end will inevitably come and, of course, it seems to a person unexpected, sudden and least of all desirable.

In view of all of the above, the question asked by the long-suffering Job becomes quite logical, acceptable and understandable: “ When a man dies, will he live again? (14th chapter). In other words: " ?".

"WHEN A MAN DIES" ... Job has no doubt that a person will certainly die: "a person dies and falls apart ..." (verse 10). The presence and power of death in the world is an indisputable fact. This is the only thing a person can be absolutely convinced of. The life of all people and each person individually, whoever he may be, usually ends in death. “And it will never be that someone remains to live forever and does not see the grave,” declares one of the sons of Korah (Ps. 48th). Leo Tolstoy wrote: Everything in the world is illusory, one death is real…».

God made the death of man a Divine necessity: “it is appointed for men to die once, and then the judgment…” (Heb. 9th chapter).

Death is the most disgusting phenomenon in nature, which people, as a rule, do not want to remember, refuse to talk about and avoid thinking about it in every possible way. ABOUT! if a person could forget about death or know nothing about it at all! But, alas! You cannot stop knowing what you know or throw out of your mind the thought of impending death.

The thought of inevitable death poisons all our earthly joys and charms of life: our well-being, health, material security, life achievements, successes and victories. A person knows: death will come and what will be left of all this?

Death is the only thing with which a person is not capable, cannot agree, reconcile, recognize it as a completely natural and normal phenomenon.

God is the source of Life and He certainly did not create man for death. It is not surprising, therefore, if in every human organism, usually consisting of many billions of living cells, each such cell protests against death, desperately fights against death, does not submit to its demands and is indignant at its violence.

But, sooner or later, death overtakes us and coolly performs its terrible deed in defiance of our self-preservation instinct, our logic, will and common sense.

Death ruthlessly and rudely tramples on everything that we bowed down to in this life: beauty, genius, strength, fame, wealth, power, etc. Having reached the halo of his greatness, Napoleon blasphemously exclaimed:

“To you, God, - the sky, and to me - the earth!” .. God did not mind. Not much time passed and the "great Frenchman" received from God two "small meters" of land ... "He was taken from the dust and returned to the dust."

The human body is an amazing instrument, an organism created by the fingers of an almighty and incomprehensible Creator. In its normal life, the body is the embodiment of health, strength, harmony, harmony, beauty. But, here death comes and everything changes radically, everything stops, everything stops: thinking, will, feelings, imagination - everything becomes lifeless and perishable.

Death is incorruptible. It is said: "a time to be born, and a time to die" ... and death exactly adheres to the due date.

Death equalizes all: “Alas! the wise one dies along with the foolish”… (Eccl. 2nd chapter). Death equated Alexander the Great with a mule driver and the wise Socrates with an illiterate slave.

Death takes back from us everything that we have acquired, what was given to us and what we used in earthly life; so: a man is born and dies empty-handed. “Just as he came out naked from his mother’s womb, so he departs as he came, and he will not take anything from his labor that he could bring in his hand” ... (Eccl. 5th chapter).

The wife of millionaire D.P. Morgan, a banker and industrialist on an international scale, while on her deathbed, ordered the servants to bring her her favorite dress. The dying woman wanted to take another look at the dress that she liked more than all the others, but there was no time for admiring the dress. When the dress was brought to her, the dying woman, in mortal horror, barely had time to grab the edge of the dress with her bony hand and immediately died convulsively. While they informed her husband about this and began to prepare the deceased for burial, the hand that grabbed the dress in a death cramp became so ossified that, after all fruitless efforts to free the dress from the hand of the millionaire, it was necessary to take scissors, cut off the dress around the fingers and with this clamped piece of cloth and bury her.

What an irony of death: of all the incalculable wealth that this woman possessed, she took with her to the grave only that insignificant piece of dress that remained in her clamped palm.

A person cannot forget about his inevitable death also because God often reminds him of this. He refreshes our memory with serious and sometimes incurable diseases, accidents, natural disasters, dangers, wars, revolutions, earthquakes, dead ends in life and many other ways and possibilities of His.

A person cannot but be interested in the question of the afterlife also because all human attempts to eliminate death turned out to be vain, naive, and ridiculous.

Remembering everything that has been said so far about death, it becomes clear to us why the sage of ancient times wanted to get a clear answer to the question: “When a person dies, will he live again?”.

It must be assumed that for the first time such a question arose in the mind and heart of Eve, who stood at the grave of her son Abel. And, since then, with the same incomprehensible mystery, this question has arisen, arises and will arise in all normal-minded people.

Question: "Will he live again?" stands before each of us today.

Philosophers and thinkers of all times tried to answer this question, but they only clothed it in their incredible and intricate conjectures, without giving humanity an exhaustive, authoritative answer.

The founders of all ancient and modern pagan religions wanted to answer this question, but they not only did not illuminate it, but, on the contrary, only obscured, perverted and confused it.

Atheist materialists of all times and all shades have claimed to have an exact answer, but instead of an answer they have presented us with a formless pile of loud but empty phrases devoid of Truth.

Atheistic fanatics and "know-it-all" scientists manipulated many hypotheses and theories, deliberately choosing only what was beneficial for their preconceived conclusions and conclusions and discarding everything that contradicted them, managed to seduce the minds of the ingenuous, with several distorted truths, still not yet tested and not confirmed.

Unfortunately, such an impudent “scientific” deceit, veiled and disguised as Truth, plunged several rising generations into the abyss of spiritual darkness and gross delusion.

Materialism in modern science, with its denials of the spiritual nature of man, has led young people to atheism and indiscriminate denial of everything that is above our fallen, vicious, carnal nature. As a result, the characteristic features of our era are unbelief, doubts, denial and animal indifference of a person to what awaits him in the afterlife. Thanks to such a primitive worldview, the circle of ideas of modern man and society and the circle of his interests is narrowed, closed and limited only by the limits of his earthly existence. Warmed up by an insatiable greed for gain, the accumulation of material and earthly goods and a reckless life, our generation has lost all its lofty, moral and spiritual ideals and risks ending up with the meaninglessness of its earthly existence, or bestial savagery.

Isn't it strange that in our time a cultured person doubts the afterlife and the immortality of his soul, allegedly for the reason that he does not have solid evidence for his faith, but then decisively refuses all the evidence offered to him? Frankly speaking, he fears most of all a reasonable, sincere "belief in God" and, of course, spiritual insight and a sense of responsibility before God for the immorality and vices that have enslaved his will. In the words of Christ: he does not go to the light, lest his works be exposed, because they are evil“… (John 3rd chapter). Hence, with all the logic of faith and with all the evidence of immortality, the modern "intellectualist" prefers to live in blind disbelief. It is paradoxical that, having renounced faith in God, he nevertheless believes, but he believes not in God, but in some kind of “non-existence” promised to him by atheistic false prophets: “You will die, they will bury you, as you did not live in the world” ...

These false teachers, false leaders and false saviors of humanity are accustomed, without any reason, to assert that the world is an arena of blind physical and chemical forces inherent in matter. (They don't care about the question: who put these forces into matter?). They even tend to believe in the immortality of dead matter, from which, allegedly, all living things originated. Such a "blind faith in blind matter" can be observed, unfortunately, not only among people who are underdeveloped, but also among those who claim to know logic and the exact sciences.

Due to precisely this illogicality and undemandingness of some modernist scientists, such words as God, eternity, soul, immortality, miracle, and others are excluded from their "scientific" lexicon.

Because of this sad thoughtlessness, some superficial people, indeed, believe that the denial of God and the afterlife is based on reason and is the result of modern increasing knowledge, rigorously verified facts, the fruit of the latest discoveries of science, the achievement of advanced thought, culture and civilization. In fact, for such a denial there has never been, is not and cannot be any "reasonable" basis. On the contrary, the denial of the Creator of the Universe has always been done contrary to reason, and people capable of such a shameless and blasphemous denial are called “fools” in Holy Scripture: “The fool has said in his heart: there is no God!” (Ps. 13th and 52nd).

The madman said - "in his heart" ... Therefore, the denial of the madman does not come from his mind, but from his heart. Man denies the existence of God not on the basis of his conclusions, but on the basis of the slyness of his vicious heart and on his hostility to God. Reason or common sense would never lead a madman to such an unfounded belief.

It is more profitable for a sinner that there is no God and His strict moral requirements, and therefore he wants to inspire himself and convince the people around him that there is no God. But, from such a personal self-hypnosis of an atheist, God will not cease to exist. Of course, every madman can go down into a deep and dark cellar and there preach to everyone in the cellar that there is no sun, but such preaching will by no means prevent the sun from illuminating the earth with its brilliance and warming it with its bright, life-giving rays. Such a preacher will be right in his assertion that “there is no sun” for him and for all those who are in the basement, but for all other people who use its graceful and beneficial services, proofs of the existence of the sun will be superfluous and even absurd. The words of an anti-religious propagandist who said that there is no God seemed to the peasant so absurd. To which the man replied: “God, you say, no? God was there a while ago, but now where did he go?”

Death. What it is? What does it refer to and what does it mean? For a child, perhaps death is a departure, the absence of the Other. Death is "going to war"; and "die" is the same as "go to war", "don't bother me", and just "leave".

Again I remember my daughter at the age of one and a half years, when she used the word "bye!" as a defense against her tormented cousin, the same age. She used it very rarely, as a last resort, when no other measures worked. Then she waved her hand to him and said "bye!". It seems that the subject's first encounter with death is the experience of the absence of the Other. There is nothing to suggest that with age the subject gains more experience with death.

The knowledge of death is still the knowledge of the absence of the Other. Death still remains closed and inaccessible to the subject, he cannot break through to it in any way, although the imperative “memento mori” tends to be obsessively repeated in culture as long as it itself exists. Why is that? Why should we be reminded of this? Maybe because not everything is clean here? What is wrong with death?

It's not like that, and it's not like that from the very beginning. Literally from the mirror stage. “It soon became apparent that the child, during this long loneliness, had found a means for himself to disappear. He opened his image in a standing mirror that went down almost to the floor, and then squatted down so that the image in the mirror went "away". The child plays with his own absence. That is, I want to say that all the philosophical reasoning of a mature person about life and death is nothing more than a cry of "Baby oh-oh-oh." Firstly, the subject is faced with the impossibility of his own absence, in this sense, death is division by zero, and secondly, he cannot NOT divide by zero, this operation is obsessively repeated, division by zero becomes the fate of the subject. So what is it? What can be that which cannot disappear? Of course, only those that never existed.

In the second lecture of the cycle "Lacan-Likbez" - "Language and the loss of the subject" A. Smulyansky shows that when the subject is represented, presented to the gaze of another, it turns into a function, and at the same time it does not exist as a subject. When the subject is not presented to the gaze, it is no more, it is not for another. So the subject is absent, but does not know about it. He is missing, he is dead, he is logically impossible, but as long as he does not know about it, everything seems to be in order. Although not all is well. There is such a thing as anxiety, and it does not lie: "preparedness in the form of fear with an increase in the energy potential of the perceiving system is the last line of defense against irritation." And now we combine castration anxiety with the impossibility of the subject, and we get that the subject is not afraid of death, but that there is no death.

In this regard, I just want to say: "Baby oh-oh-oh." Here's another way to understand the death drive. A return to a former state that never existed before. Playing with impossibility, with the very basis of the subject. Isn't this the impossible question the analysand asks himself? Isn't this the question he obsessively repeats in all sorts of variations, editions? Just as the dream of a traumatic neurotic inspires fear, which is not enough there to heal from fear (breakthrough into the Real?), So games with a mirror are designed to show that the subject may not exist, and this convinces him that he is. Fear, by the way, always works that way. The subject receives the object of fear, albeit in the form of denial. He does not even recognize in this object the object of his desire.

If we do not forget that the subject and the organism are completely different things, it will become clear that in relation to the organism it is quite possible to speak of biological death. Freud reminds us of the biogenetic law, that is, that ontogeny is the repetition of phylogeny. At the same time, drives and obsessive repetition reveal their connection, which consists in the fact that the very nature of drives is very obsessive and conservative, which conflicts with their other side - the desire for variability and progress.

“Attraction, from this point of view, could be defined as a striving present in a living organism to restore some previous state, which, under the influence of external obstacles, a living being was forced to leave, a kind of organic elasticity, or, if you like, an expression inertia in organic life. Conservatism is against progress - death is against life, and Freud, having established these poles, further deconstructs the concept of "life", then shows that these are not opposites at all, and they have, in general, one goal. Life is not the opposite of death, it is only a temporary deviation from it.

This is a workaround to death, an attempt to avoid "short circuiting". The organism, Freud notes, wants to die, but only in its own way. After this clarification, it becomes obvious that the life and death drives do not represent a primitive dichotomy, a binary opposition, any archetypes or primary mythological symbolism like "yin-yang" cannot in any way be deduced from this. Freud takes a different path, "not short-circuiting", not "short-circuiting" on Eros and Thanatos. His thought does not die in the mythology of the Manichaean oppositions; it follows a more complex path.